The June 2021 BLS Jobs Report showed solid job growth in most sectors, continuing a gradual upward trend, with a net gain of 850,000 jobs added to the U.S. economy. As shown in the graph below, we still have a long way to go before we recoup the jobs lost throughout 2020, but after revisions, June was 2021’s strongest month of job gains yet.

You might also notice a difference between last month’s graphs and this month’s graphs, and it relates to a note in the lower left corner: “Shaded areas indicate U.S. recessions.” Compare the graph above to the same one below from last month’s analysis:

This note said that “U.S. recessions are shaded; the most recent end date is undecided.” As you might have guessed, this means that the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) made a determination regarding the duration of the 2020 pandemic recession.

The 2020 Recession

According to the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee, the 2020 recession ended in April 2020, and the economy has been in expansion since May 2020. While the NBER doesn’t pinpoint exactly when a recession begins or ends, they generally identify the months in which broader economic shifts occur. According to their announcement:

The NBER chronology does not identify the precise moment that the economy entered a recession or expansion. In the NBER’s convention for measuring the duration of a recession, the first month of the recession is the month following the peak and the last month is the month of the trough. Because the most recent trough was in April 2020, the last month of the recession was April 2020, and May 2020 was the first month of the subsequent expansion.

These “peaks” and “troughs” refer to relative high and low points in several economic indicators, such as employment levels, gross domestic product, income, and sales figures. Below is a rough depiction of how introductory economics courses often visualize the “business cycle” – a phrase used to describe the ups and downs that economies experience over time – which has “peaks” and “troughs” at high and low points, respectively.

The reality of the business cycle is obviously more complicated than this simplified diagram implies, where the cycle’s timing, heights of peaks, depths of troughs, are difficult to predict, and often defy expectations. Before the 2020 recession, we saw the longest period of expansion in U.S. history, which lasted more than a decade after we began to recover from the Great Recession. The 2020 recession also set a record for being the shortest recession in U.S. history. As the NBER put it:

The previous peak in economic activity occurred in February 2020. The recession lasted two months, which makes it the shortest US recession on record.

Although multiple economic indicators are monitored when examining the business cycle, these trends are quite apparent when examining U.S. employment levels.

Notice some differences between the two recessions and subsequent expansions? The Great Recession saw employment levels consistently falling for more than a year, before taking several years to reach prior peak levels. The 2020 recession lasted a couple months before Congress took meaningful action to pass Coronavirus relief and economic stimulus legislation, and subsequent bills were passed when the recovery began decelerating. The U.S. response to the 2020 recession was not perfect, but given the robust, sustained stimulus deployed throughout the pandemic, lawmakers appear to remember at least some of the lessons learned from the Great Recession.

We still have millions of jobs to recover before we return to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity – with 9.5 million total unemployed people now, compared to the 5.7 million in February 2020 – but turning the corner from recession into expansion is a necessary first step. The NBER puts this into perspective:

In determining that a trough occurred in April 2020, the committee did not conclude that the economy has returned to operating at normal capacity. An expansion is a period of rising economic activity spread across the economy, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. Economic activity is typically below normal in the early stages of an expansion, and it sometimes remains so well into the expansion.

How long it takes to return to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity will depend on how strong our recovery is. With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at June’s jobs numbers.

June 2021 Jobs Report

As mentioned previously, with 850,000 net jobs gained, June 2021 currently holds the record for most jobs added in a single month for 2021. The graph below helps compare June’s gains to those of the other months thus far.

Current revisions put March 2021 in second place, with 785,000 jobs added to the U.S. economy. Leisure and hospitality jobs once again topped the charts with 343,000 net jobs gained in that industry, but government jobs also added 188,000 jobs, as shown in the table below.

Unfortunately, construction jobs posted the third straight month of net losses, despite relatively strong growth in March, though the losses decreased to only 7,000 jobs lost throughout June. Despite the motor vehicles and parts industry posting a net loss of 12,300 jobs, most of the other industries show modest growth, as shown in the chart above. Hopefully the upward trend continues throughout July, but with COVID-19 cases surging again, future results remain uncertain.

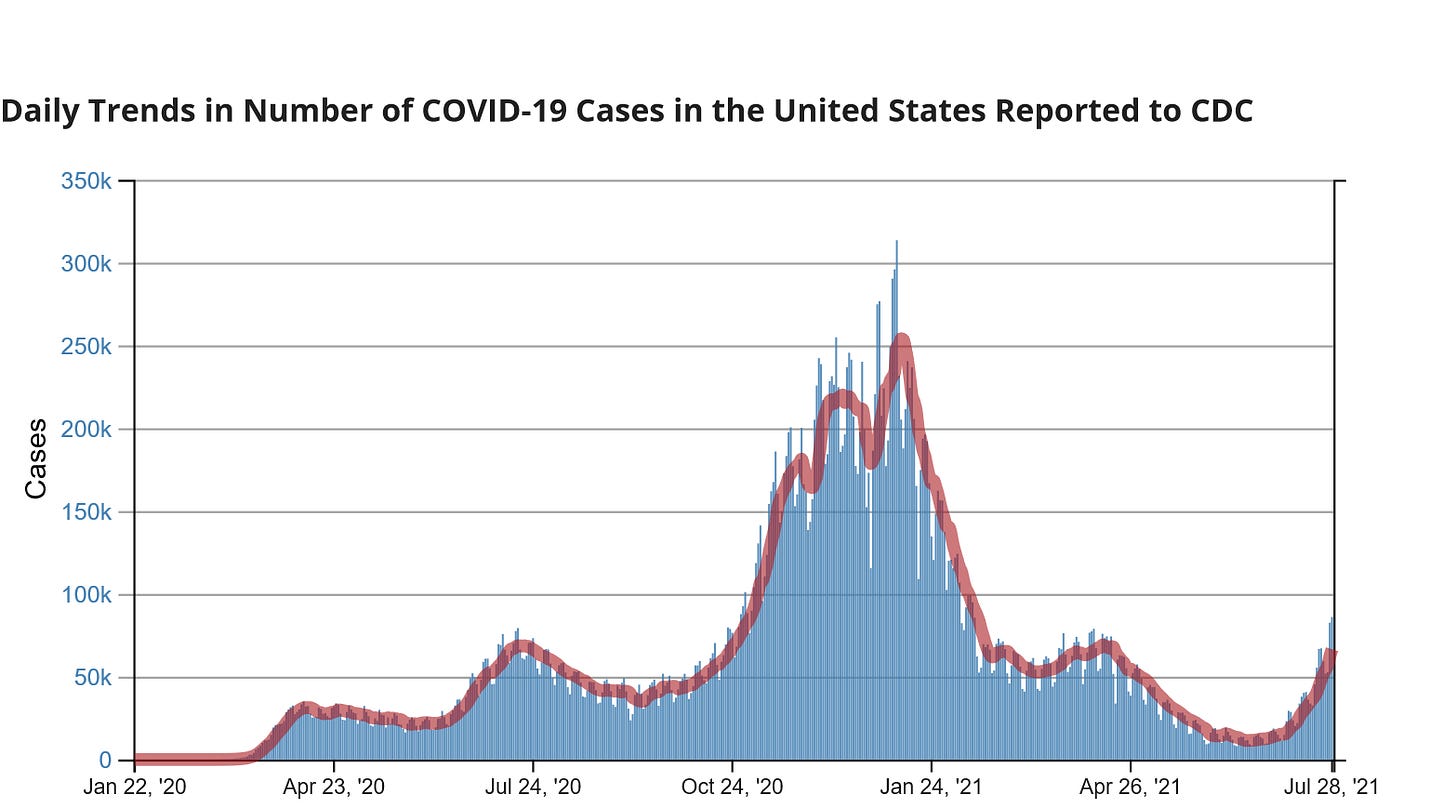

You can compare 2021’s strongest numbers yet to the strongest jobs report of 2020: June of last year. Optimists were hopeful for a stronger, sustained economic recovery after coronavirus cases began to fall throughout the Spring of 2020, and the U.S. economy added nearly 5 million jobs, but lifting restrictions proved to be premature. As you can see in the graph below, the second wave of COVID-19 cases began to rise in June before peaking sometime in July. With the Delta variant of COVID-19 spreading throughout the country, we’re approaching similar levels of new cases as we reached one year ago.

Another troubling sign is that the downward trend in the percentage of long-term unemployed reversed in June, and unemployment benefits for these workers will expire soon. The graph below shows that 42.1% of unemployed people have now been unemployed for 27 weeks or longer.

The overall unemployment rate rose slightly – from 5.8% to 5.9% – despite the economy adding jobs, due to more people entering the labor force looking for work. While the labor force increased, the labor force participation rate was flat, remaining at 61.6% in June. Although there are some concerning signs, broader trends are continuing a steady incline.

Three-Month Trends

Most industries are steadily adding jobs, as you can see in the following chart. Construction is one of the few industries losing jobs, but with news of a potential infrastructure deal approaching finalization, hopefully this trend will soon be reversed.

Using data tracked in BLS tables like we discussed earlier, I once again graphed the three-month average job gains after the most recent revisions. While it might be tough to spot April’s average being revised slightly down, and May’s being revised up, it’s easy to see that there is a gradual upward trend to the averages overall.

We will soon have July’s jobs report to evaluate whether this upward trend persists despite rising Coronavirus cases. I apologize for this article coming so late in the month, but I spent most of the month working on articles analyzing the For the People Act, which we urgently need to pass. I look forward to examining July’s data with you once it becomes available, and you can follow me on Twitter for more frequent updates, but I want to briefly share some news about a topic we discussed last time.

Update on Prematurely Cancelled Unemployment Benefits

I wrote about the “labor shortage” debate last time, how Republican governors across the country were preventing their states’ unemployed workers from collecting the unemployment insurance (UI) benefits they are owed, and how the workers of Indiana were suing the state to reinstate these benefits. I have good news, or at least a silver lining, from the state of Indiana and other states affected by these foolish governors.

Not only did Indiana workers win their case, but more states are joining the struggle to reinstate UI benefits. I’m now aware of workers in 8 states – including Indiana, who is now joined by Tennessee, Florida, and Arkansas more recently, but also Maryland, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Texas – who are joining class action lawsuits to receive the UI benefits they are owed. I hope they receive the money they are owed soon because this delay has serious consequences.

Preliminary data shows that, not only have these Republican governors not spurred job growth by their actions, but prematurely cancelling UI benefits is also causing families to have trouble making ends meet. According to analysis by Economics Professor Arindrajit Dube:

Overall, the mid-June expirations of pandemic UI seem to have sharply reduced the share of population receiving any unemployment benefits. But this doesn’t seem to have translated into most of these individuals having jobs in the first 2-3 weeks following expiration. However, there is evidence that the reduced UI benefits increased self-reported hardship in paying for regular expenses. Of course, this evidence is still early, and more data is needed to paint a fuller picture.

I will certainly continue to monitor new data as it becomes available, but it sounds like all these Republican governors have accomplished is inflicting more unnecessary suffering. Many UI benefits already expire on Labor Day – a cruel Labor Day gift for the millions of workers who are likely to remain unemployed, unless we have some miraculous jobs reports in the next few months. Still, September 6 is about a week and one month away, and suddenly this arbitrary deadline is once again just over the horizon.

Will Congress act again to prevent unnecessary suffering? Or will they go on recess and say, “Let them eat cake”?

Thank you for reading my newsletter and taking the effort to learn about making the world a better place. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can make progress towards a more just economy.

-JJ

Updated 6/27/2022 - Updated captions for graphs and tables

Updated 9/30/2021 - Changed dark-themed graphs for graphs with white backgrounds; added captions to the graphs I created.

Updated 9/21/2021 - Removed introductory paragraph which was mostly intended for email recipients; also removed update date at the top of the article; italicized sign-off paragraph.

Updated 7/31/2021 - Clarified sentence regarding UI benefits expiring on Labor Day, noting that “Many UI benefits already expire on Labor Day”, but not necessarily all UI benefits. This way, the wording is consistent with the phrasing used in my original reporting on the American Rescue Plan. The original sentence in this article read, “UI benefits already expire on Labor Day”.