Unemployment and Inflation Basics

An Introduction to Macroeconomic Issues

After covering so many concrete details of current events, including the U.S. response to the Coronavirus pandemic throughout the Coronavirus Relief and Economic Stimulus series, I wanted to briefly return to a bit of economic theory and fundamental concepts. Whether you are learning some of these terms for the first time, brushing up on some concepts you’re familiar with, or simply seeing another perspective on economic fundamentals you already know and understand well, I hope readers of all backgrounds gain some valuable insight.

Economic Indicators

While examining ways in which we might make progress towards a more just economy, I’ve been keeping an eye on certain economic indicators, or statistics which help us analyze economic activity. Big-picture statistics like unemployment and inflation indicators help us understand broader trends in the overall economy. The central bank of the United States—the Federal Reserve (or “the Fed”)—also uses such statistics in trying to accomplish its congressionally mandated goal: maintaining stable prices and full employment. As important and frequently cited as these economic indicators are, some of the details are still often misunderstood. Let’s clarify some of these concepts so we can begin future discussions on the same page.

Unemployment Rate and Other Labor Force Indicators

One of the most frequently mentioned economic indicators is the unemployment rate. Most readers will probably be familiar with this statistic, but there are important details that I also want to highlight. For instance, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) covers such details on its Frequently Asked Questions page: “People with jobs are employed. People who are jobless, looking for a job, and available for work are unemployed.” To calculate the unemployment rate, we need a third piece of information: the amount of people in the labor force.

The labor force includes people who are employed and unemployed, but not those who aren’t seeking a job. Because the unemployment rate is calculated by taking the number of unemployed people and dividing it by the total labor force, analyzing the unemployment rate alone can miss part of the full picture. Despite its limitations, the unemployment rate is still a crucial part of understanding broader trends in the overall economy, as you can see in the graph below from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) website.

Shaded regions on the graph show “recessions”, which are basically periods of economic contraction rather than growth. These economic downturns frequently coincide with spikes in unemployment. It may not necessarily come as a surprise to see just how devastating the job losses in 2020 were, but even though we are on our way to an economic recovery, and expect strong economic growth for 2021, there is still a long way to go.

Beyond just the standard unemployment rate showing signs that our economic recovery is incomplete, the BLS also makes note of certain complicating factors. One such complication is unemployed workers being misclassified in their survey data. According to the March 2021 Employment Situation Summary, the BLS noted that, “As in previous months, some workers affected by the pandemic who should have been classified as unemployed on temporary layoff were instead misclassified as employed but not at work.” It might seem like semantics at first glance, but furloughed workers are not all necessarily expecting to return to work immediately.

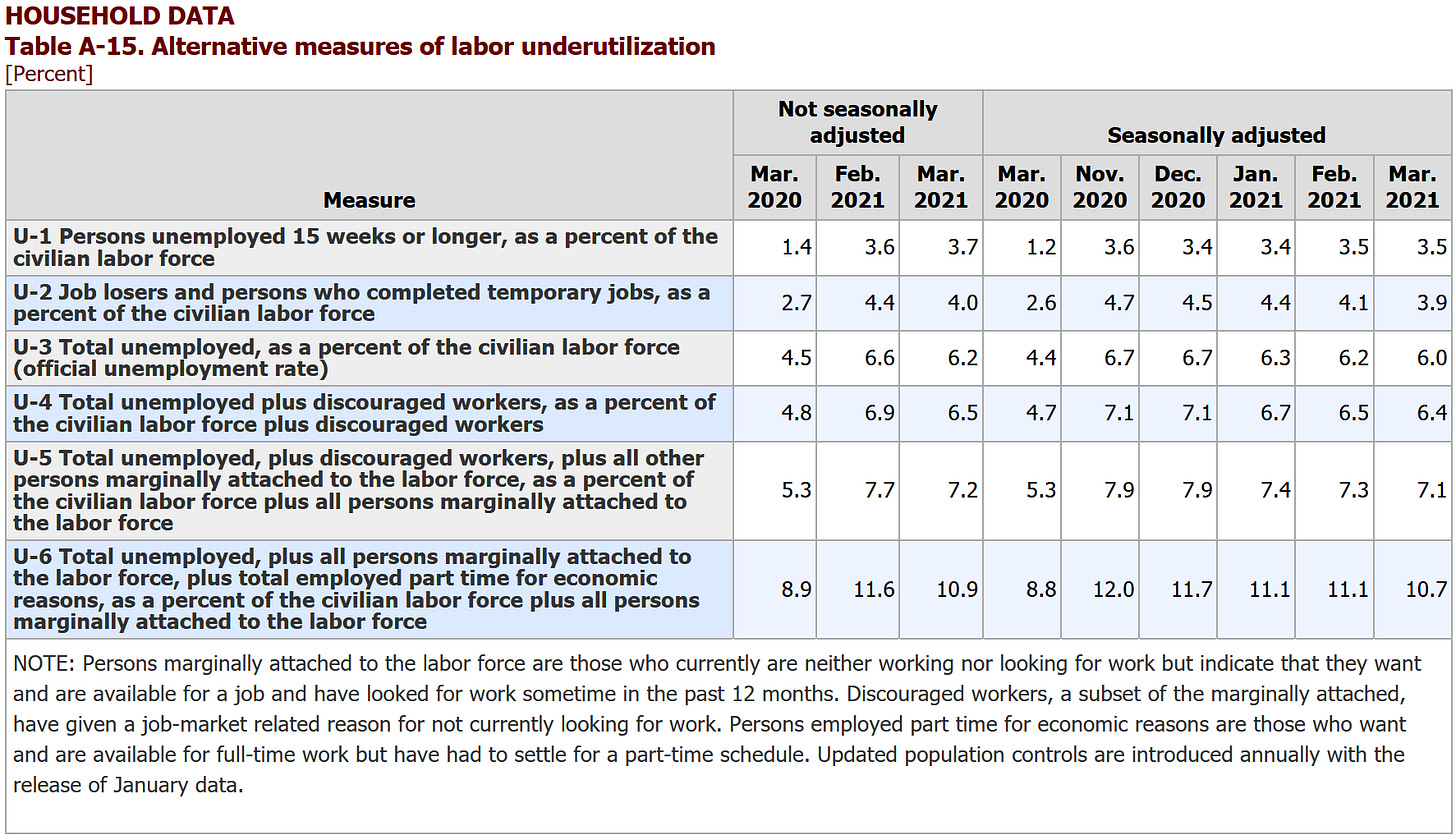

The BLS also compiles data on another type of complication known as labor “underutilization”, including people who are not completely unemployed but are underemployed. You can see in the table below that unemployment rates among various groups are broken down into six groups, U-1 through U-6. The official unemployment rate that you see in headlines is U-3.

Like the note at the bottom of the BLS table mentions, underemployed workers include people who are essentially working part time due to economic reasons, but would otherwise prefer to work full time. Statistics like U-4 through U-6 also track other groups of people not included in the official U-3 unemployment rate. This is important because, without properly accounting for people who are no longer actively seeking work, or who have otherwise fallen out of the labor force, the unemployment rate can be underestimated.

Officials like Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell have also alluded to these types of underestimation several times since the pandemic began, including as recently as last February. While the BLS reported its standard unemployment rate of 6.3% for January 2021, Yellen and Powell estimated that this “true” unemployment rate may have been between 9% and 10%. They arrived at this estimation by adjusting for both the misclassifications we discussed, and also people who are no longer in the labor force. Business Insider recently performed similar calculations to estimate that March’s 6.0% official rate is likely closer to 8.7% after adjustments.

Because of these types of complications, when trying to paint a clearer picture of the economy, it helps to analyze other economic indicators in addition to the unemployment rate. You may recall our discussion of such statistics in the article covering the December 2020 Coronavirus relief bill and the slowing economic recovery at the time, where we examined the falling labor force participation rate (LFPR). This indicator essentially shows what percentage of the total population is either employed or actively seeking a job.

As shown in the graph below, the LFPR fell precipitously in March and April of 2020, and has since rebounded modestly, but it still shows an overall downward trend since the turn of the century. On the bright side, March 2021 has shown some decent improvement, so hopefully we can maintain this momentum and begin to make up for lost ground.

Another similar economic indicator we can analyze is the employment-population ratio. As you can see in the graph below, this indicator follows similar overall trends as the LFPR, but has fewer fluctuations along the way. Visually speaking, it basically results in a less jagged line with smoother peaks and valleys. Despite generally having smoother trends, both the LFPR and employment-population ratio had steep cliffs in early 2020 as the Coronavirus pandemic began to take hold of the economy.

While the unemployment rate is an important economic indicator, the labor force participation rate and employment-population ratio should also be considered when trying to paint a complete picture of the economy.

If you want to see how our employment situation has changed since 2021, check out my series on BLS Jobs Reports below for analysis and related news stories.

It is also important to consider the purchasing power these people in and out of the labor force have, which brings us to the next set of economic indicators surrounding price stability.

Inflation and Price Stability Indicators

Another key indication of how the economy is faring can be seen in how stable prices are, or how much inflation (or deflation) occurs in the prices of goods and services. While the details surrounding inflation can be somewhat complicated, the general idea is fairly simple at its core.

To illustrate the concept of inflation in an overly simplistic but hopefully understandable way, imagine everything suddenly costs twice as much but everyone has the same income as before the prices increased. This dramatic loss of purchasing power – where a person in this situation would suddenly be able to afford only half the goods and services they previously purchased – is an exaggerated example of what generally happens over several years, but it still conveys the key concept underlying inflation: loss of purchasing power. While you might recall stories of hyperinflation from your history classes about Weimar Germany before World War II, where purchasing a loaf of bread suddenly required a wheelbarrow full of cash, most developed countries experience slow, gradual inflation over time.

Most people are less familiar with deflation, but the concept is similar to inflation, except that overall price levels decrease over time rather than increase. Although lower prices might sound like a good thing for consumers, deflation can have detrimental impacts on the economy. If everyone begins to expect lower prices in the future, then people might delay purchases they would have otherwise made. Widespread decreases in consumption often cause further economic slowdowns, leading to even lower prices, and the cycle can continue to spiral out of control. Most countries use virtually every tool at their disposal to avoid this type of deflation cycle from occurring, so for these and other reasons, they try to maintain moderate levels of inflation instead.

Updated December 27, 2021

Here in the United States, the Federal Reserve monitors inflation and sets their “target” at around 2% every year. This would mean, if we were to hit this target of 2%, that something you bought for $5.00 last year might cost $5.10 next year. In trying to reach this target, and tracking price fluctuations over time, the Fed has mutliple tools at its disposal.

The Federal Reserve monitors consumer spending levels by examining data on Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) prepared by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. This data set helps track inflation even if consumers begin changing their habits, such as substituting beef with chicken or vice versa when one becomes more expensive.

The Fed also uses data on the prices of a variety of goods and services—such as the index maintained by the Bureau of Labor Statistics known as the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—to help measure changes in overall price levels over time. The graph below shows percent changes in the CPI from the year before, and displays it from 1948 through the end of 2020.

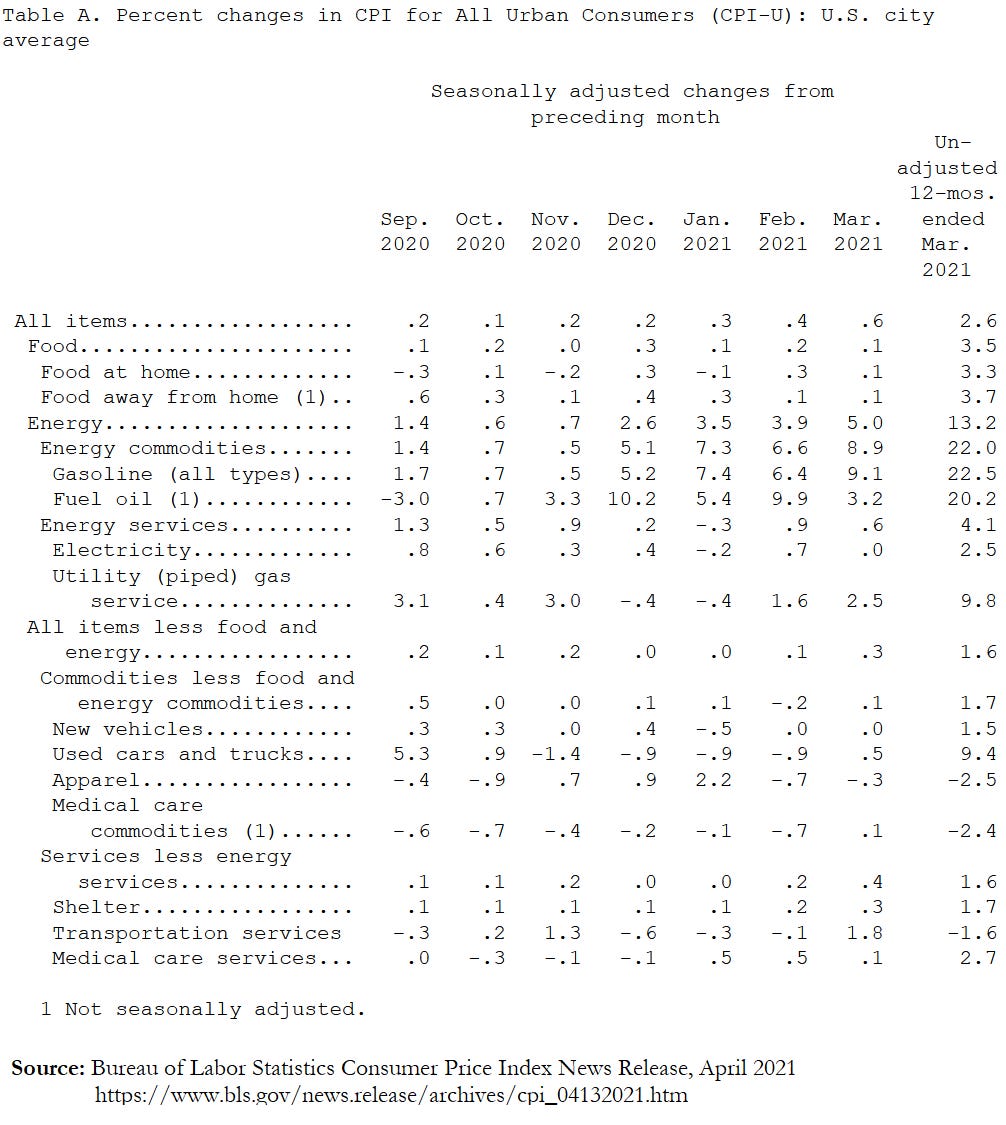

The “basket” of goods tracked in the CPI contains a variety of products and services, including food, energy, medical care, transportation, and other categories. See the table below for a look at March 2021’s breakdown of changes in CPI price levels. You may also notice that the graph above says that it is the “Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers”. Urban prices are usually examined for broader price stability due to regional disparities in certain rural areas, where access to certain resources can be scarce, which would cause price fluctuations in that area but not necessarily others.

If we take it a step further and remove fluctuations in food and energy prices, since their prices tend to be the most volatile in the “basket” of goods measured in the CPI, we arrive at the “core” rate of inflation, as seen in the graph below.

Updated July 10, 2022

Although you can see inflation spiked in the 1970s and early ‘80s, when it exceeded 10% multiple times, inflation has generally been floating around 1% to 3% throughout the 21st century. Zooming in on this past decade—i.e., between early 2011 and early 2021—you can see in the graph below that the core inflation rate averaged roughly 1.91% every year.

One tangential but important concept for all workers in the U.S. to keep in mind is that, during periods in which we are hitting our “target” rate of inflation, if you are not receiving at least a 2% raise on average every year, the real purchasing power of your wages or salary is decreasing due to inflation. Even greater raises are required to maintain purchasing power during periods of higher rates of inflation.

In other words, if you are still being paid the same amount of dollars as the year before, and each of those dollars is trying to purchase goods and services which now cost between $1.02 and $1.10 on average—after costing $1.00 last year—you are effectively unable to purchase the same amount of goods and services as you were able to last year. Keep this aspect of inflation in mind as you negotiate raises or have your voice heard through collective bargaining.

In addition to looking at inflation data from the past, there are also ways of forecasting future inflation. Using data from the U.S. Treasury Department, the Fed makes predictions about what they expect the average rate of inflation to be over the next ten years. The graph below of the “Ten-Year Breakeven Inflation Rate” shows estimates are currently at roughly 2.3%, but it rarely ever went above 2.2% in recent years, and did not exceed 2.4%.

Although prior results certainly do not guarantee future outcomes, and even experts are not certain why inflation had remained low for so long before the pandemic, I still believe that inflation is a risk that our nation can manage. A relatively short-term increase in inflation may occur, and the Federal Reserve is prepared to allow inflation to exceed the 2% target if necessary, but when I initially wrote this article, long-term, sustained increases in inflation rates were doubtful. However, as you can read in further detail in my latest article on inflation, the entire world is struggling to keep prices stable in 2022.

Despite my confidence in our long-term ability to mitigate the risk of sustained inflation, economists and officials at the Federal Reserve alike have admitted to fundamentally misunderstanding certain economic dynamics. Looking back at when I initially published this article last year, I must admit that I also did not fully understand the extent to which the fragility of global supply chains would leave the entire world vulnerable to inflation.

While I could briefly address some of those economic mysteries here, and what the latest research into solving them includes, I will save discussing them in more detail for future articles. I hope this look at the basics will nevertheless leave readers feeling ready to explore some of the more difficult topics.

Latest Article on Inflation

Updated 6/27/2022

Now that readers will hopefully have a decent understanding of the basics of unemployment and inflation statistics, and now that more data is available, I wrote an article examining changes we’ve seen since the pandemic began.

Read more about why, after examining recent studies and data, I concluded that:

Inflation isn’t just happening in the United States

Consolidated markets and corporate profiteering exacerbate inflation

Pandemic relief in the U.S. wasn’t a mistake

Combating inflation does not require enduring unnecessarily high rates of unemployment for years to come

Beyond clarifying misconceptions, I also highlighted how supply-chain disruptions—particularly in the oceanic shipping industry—have contributed to global inflation. I wrapped up this extensive article with a brief discussion of what the path forward for the U.S. may look like.

Please feel free to reach out and leave a comment to let me know if you have any questions about these concepts, if you would like me to cover certain aspects of inflation and unemployment in further detail, or if you have any other questions or comments about progressing towards a more just economy.

Thank you for reading my newsletter and taking the effort to learn about making the world a better place. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can make progress towards a more just economy.

-JJ

Updated 7/10/2022 - Clarified period during which CPI inflation averaged 1.91% per year; added mention of “target” inflation during discussion of real purchasing power; updated transition to final section of the article which includes a retrospective on supply chain vulnerabilities I did not fully account for when first writing this article last year.

Updated 6/28/2022 - Rephrased summary of latest article.

Updated 6/27/2022 - Added captions to graphs and tables; added link to latest article on inflation.

Updated 12/27/2021 - Added section on PCE; added link to Jobs Report Analysis collection; updated Future Articles section.

Updated 10/7/2021 - Removed the updated date from the top of the article; italicized the sign-off paragraph.

Updated 6/11/2021 - Changed “April 2021 Employment Situation Summary” to “March 2021 Employment Situation Summary”. Although the report was issued on April 2, 2021, the employment data analyzed is from March 2021. I use this format for future articles, so I updated this article for consistency.