CARES Act Relief and the Need for Economic Stimulus

Coronavirus Relief and Economic Stimulus Vol. II

Greetings, and welcome to the third article of the Economic Justice and Progress Newsletter, and the second entry in my Coronavirus Relief and Economic Stimulus series. This picks up where we left off in the first article in this series discussing the economic impact of the pandemic and Congressional policies delivering relief to working families.

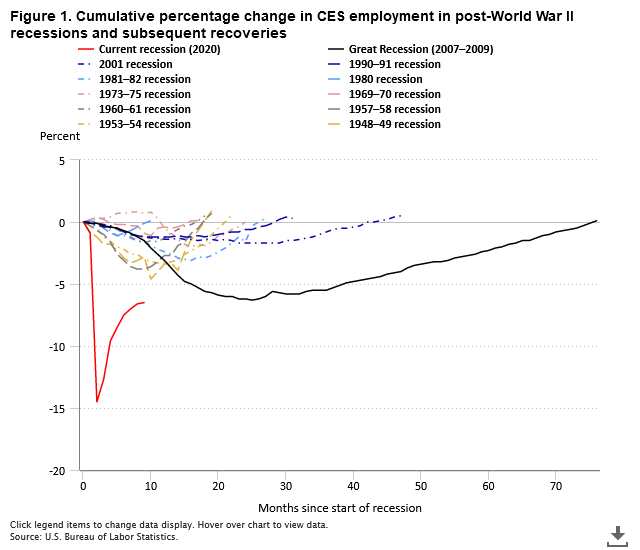

We previously examined economic studies about the impact of the Cornavirus pandemic and BLS graphs showing the millions of job losses in early 2020 and the slowing economic recovery leading into 2021. Now I want to take a look back and show how we’ve been in this type of situation before, that we can do something now to avert a worse crisis, and make the case that doing so is the correct economic and political decision to make.

As we welcome the new administration into the White House, now is the time to deliver meaningful results for working families across America. To get a better understanding of what we’ve done correctly in the past, and what we can improve upon in the future, let us now examine the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, more commonly referred to as the CARES Act.

Core Provisions of the CARES Act

The CARES Act’s core relief spending provisions affecting the broadest groups of working families delivered $1,200 direct Economic Impact Payment checks to most adults earning $75,000 or less, plus $500 for qualifying children, and also provided a generous $600 per week in federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits for four months on top of standard state UI benefits. Apart from the payments for children—which is now $600 per qualifying child under the relief bill passed in December 2020 instead of $500—these amounts in the CARES Act are double the amounts provided by the recent Coronavirus relief legislation.

The CARES Act also provided other types of funding, similar to how the recent Coronavirus relief legislation did. Here is a quick look at the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) accounting of all the various spending categories included in the CARES Act and other related bills:

I may cover more of these other spending categories in a future article, but I want to first examine the overwhelmingly positive aspects of these provisions affecting the broadest groups of working families, which I feel should also be repeated in future Coronavirus relief bills. You can see that $375 billion was appropriated for the UI benefits and $282 billion for the Economic Impact Payments. After reviewing the findings of several economic studies analyzing the impact these “transfer” programs had, I’m confident you will agree that Congress needs to deliver more direct relief and bolster unemployment benefits again to alleviate the unnecessary suffering and further ward off the economic downturn we discussed previously.

Relief and Economic Stimulus Helps Everyone

For insight into the CARES Act and the impact it had on working families and the broader economy, we can turn once again to the economic studies summarized in Acts of Congress and COVID-19 by Elena Falcettoni and Vegard Nygaard, like we did throughout the first article in this series. As you will see, the findings of these studies consistently show that, despite its flaws, the CARES Act helped working families survive and stimulated the economy, which helps everyone.

These empirical analyses of the unemployment benefits and direct payments summarized in Falcettoni and Nygaard’s paper show how providing relief to working families boosted consumption spending, which therefore stimulated the overall economy in the process. For example, one study cited in the summary indicated that, “Both the transfer programs (EIP, UI) and PPP [Paycheck Protection Program] boost aggregate consumption throughout the lockdown and in its immediate aftermath.” Another paper demonstrated that these payments also reduced the amount of economic output that would have otherwise been lost due to the pandemic-induced recession.

Last time, during the first article of this series, we discussed how the Coronavirus disproportionately impacted workers who were already economically vulnerable before the pandemic began, but these reports’ analyses show how the CARES Act transfers helped remedy some of these vulnerabilities. Evidence includes the findings in the Cortes and Forsythe study which shows:

Workers who were previously in the bottom third of the earnings distribution received 49% of the pandemic-associated UI and CARES benefits, reversing the increases in labor earnings inequality. These lower-income individuals are likely to have a high fiscal multiplier, suggesting these extra payments may have helped stimulate aggregate demand.

This evidence shows that just under half of the benefits went to the poorest third of workers. It also shows that, because this struggling demographic is often forced to forgo or ration their necessities due to budget constraints, they also spend a large portion of any additional funds they receive—stimulating the economy in the process —hence their likelihood of having a “high fiscal multiplier”. Another paper titled Income and Poverty in the COVID-19 Pandemic had similar findings:

Our results indicate that at the start of the pandemic, government policy effectively countered its effects on incomes, leading poverty to fall and low percentiles of income to rise across a range of demographic groups and geographies. […] [G]overnment programs, including the regular unemployment insurance program, the expanded UI programs, and the Economic Impact Payments, can account for more than the entire decline in poverty, which would have risen by over 2.5 percentage points in the absence of these programs.

These transfer programs lifted people out of poverty, prevented others from falling into poverty, and stimulated the economy. Stimulating the economy in a way that also lifts people out of poverty and boosts overall consumer spending, in a consumer-driven economy like we currently have in the United States, ultimately helps everyone across the country. I may write a separate article in the future which addresses more theoretical framework further supporting this notion of growth from the bottom up—and perhaps another article which rebukes the nonsense surrounding provably false “trickle down” economic theories—but in the interest of focusing on more concrete evidence for this article, consider the chart below. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) collects data comparing the trends between changes in consumer spending and total economic output, or gross domestic product (GDP).

Because I want to continue making graphs more accessible to readers unfamiliar with certain formats, the blue bars show changes in consumer spending and the orange bars show changes in total output, or GDP. Bars going above the line marked “0” denote increases and bars going below represent decreases. Notice how the bars always go in the same direction during a given time period, and frequently are roughly the same size. This trend is particularly visible in a year as tumultuous as 2020 was, but the correlation between consumer spending and the broader US economy is clear.

BEA data also shows, as you can see below, that consumer spending consistently accounts for nearly 70% of GDP, with the other 30% or so being varying amounts of investment spending, net exports, and government spending.

However, despite the positive impact the CARES Act had, particularly the direct relief for working families who keep the economy running, it was still far from perfect. We can learn about what future relief should include and what we should avoid by examining both the positive aspects and the shortcomings of the CARES Act.

Shortcomings of the CARES Act Transfers

Significant improvements could have been made to the CARES Act—especially the programs we didn’t discuss yet, but I will save that for a future article—but many of the potential improvements to the transfer programs boil down to expanding the benefits already provided and improving the execution of these programs.

For instance, although these relief payments authorized by the CARES Act helped keep people from falling into poverty and even lifted others out of poverty while benefits lasted, this trend reversed once the benefits expired at the end of July 2020. The increase in poverty after the expiration of these benefits ultimately increased current poverty rates beyond pre-pandemic levels according to another study. This was avoidable, and Congress has the legislative ability to prevent such unnecessary suffering again.

The paper titled Modeling the Consumption Response to the CARES Act also provides more economic context for the consumer spending data we discussed earlier in this article. While the enhanced UI benefits and direct payments boosted overall consumer spending, this study examined spending patterns for different groups of workers, including workers who are still employed and those who are actively seeking work.

This detailed examination reveals that, unfortunately, consumers who fall under the long-term unemployed category had to stretch their direct relief payments over a longer period of time, limiting their ability to spend more cash immediately—and do so with confidence—since future relief was and still remains uncertain to this day, nearly a year later. The more generous, and often more quickly received, UI benefits therefore had a greater impact on spending for these households. A study, which estimated what the optimal amount of direct relief payments should have been, concluded that even the $1,200 checks were not large enough, especially for low-income families. We can and should make additional relief a reality.

What’s more, our states’ unemployment insurance systems, and our federal tax filing system—through which the Economic Impact Payments were issued—had administrative and technical flaws of their own. The IRS has been underfunded for years and had trouble reaching non-filers—i.e., people who did not file a tax return for either 2019 or 2018—which frequently includes many of the most marginalized groups in our society, such as people who are unhoused, do not have access to the internet, or do not have a bank account.

The GAO report referenced earlier in this article states that the Social Security Administration and other government agencies helped reach some non-filers, but they only sent taxpayer data and not information about their qualifying children, leaving the families of up to 450,000 qualifying children without the additional $500 of relief per child. These families had to instead use the IRS non-filer tool to manually request the money, assuming they were even aware they qualified for additional relief and also had access to the internet, which is not guaranteed for these marginalized groups.

President Biden signed an executive order on January 22, 2021 which is supposed to facilitate the process of reaching those who still have not received their full relief checks, but many of these families might have been among those lining up at Food Banks while they waited for relief to reach them. Biden also includes adult dependents in his latest $1.9 trillion proposal for another Coronavirus relief bill, which often includes students over the age of 17, disabled people, and other struggling groups who would not qualify for direct checks under either the CARES Act or the recent Coronavirus relief bill.

Still, Biden’s proposal remains a framework of requests, and as of the time this article was written, we still do not have a formal bill from Congress, while the clock is ticking for working families across America. [Note: see the May 31, 2021 update at the end of the article.] Speaker Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Schumer did, however, take the first step towards introducing a formal bill on February 1, 2021. Pelosi and Schumer announced a joint resolution giving both the House of Representatives and the Senate a path towards passing a Coronavirus relief bill using a process known as budget reconciliation, which would only require a simple majority of 51 votes to pass in the Senate. Although this is only the first step of the process, I hope that Congress will act swiftly to pass another long overdue Coronavirus relief bill.

Perhaps the Biden administration will also address the unemployment infrastructure which runs on aging computers, and if you’ve ever tried to complete even simple tasks on a computer with a lot of “mileage”, you know that this inevitably leads to unnecessary delays at every step of the process. Other technical difficulties that caused delays were the unemployment websites which would frequently malfunction when unprecedented levels of new claims flooded the systems after millions lost their jobs. These systems are necessary for our economy even during relatively normal times, and with working families falling through the cracks, now is the time to start fixing these underlying problems.

Another problem which received a great deal of attention—although it pales in comparison to not sending relief out to those who needed it—was when the IRS sent checks out to qualifying taxpayers who filed taxes in 2019 or 2018 but passed away before the CARES Act passed in March 2020. According to the GAO report, IRS officials concluded that they did not have the legal authority to deny these qualifying taxpayers their checks, even if they were already deceased, because of how the law was written.

While the headlines decrying $1.4 billion in checks being sent out to deceased taxpayers might have initially sparked outrage, when taking a closer look at the details, this amounts to just under 0.5% of the total $282 billion appropriated, which is a relatively low margin of error for such a large program. I would also argue that this was the appropriate decision for the IRS to make, given the alternative.

The IRS ultimately decided, when confronted with the decision to either send relief checks to all those who qualify or delay the whole process and make sure that the deceased taxpayers did not receive the checks, that they should send out checks to everyone who qualified as quickly as possible, and simply notify the living relatives of deceased taxpayers how to return those funds. Again, in my opinion, this was the correct choice—given the alternative of otherwise delaying relief to those who need it as quickly as possible—and this type of decision erring on the side of quick relief should always be the default choice should similar situations arise in the future. It still does not absolve the IRS of its responsibility to reach out to those who qualified but still have not received relief, but now you know that the causes of these shortcomings are attributable to separate underlying problems.

In addition to updating our administrative infrastructure to shore up such failings, I would further argue that: the direct relief payments should have been paid out monthly rather than once; the expanded unemployment benefits should have lasted longer; more effort and resources should have been spent making sure the transfer payments reached more people, rather than being inordinately preoccupied with “means testing” working middle-class families who supposedly should not qualify; and these payments should have continued until significant, measurable progress gets made towards stopping the spread of the virus, rather than arbitrarily ending benefits prematurely in July 2020—or any other haphazardly chosen date—while American workers needlessly suffer.

After recent elections, we collectively have the political power to deliver relief to working families across America, now that Democratic have majorities in Congress in addition to a new administration in the White House, and we can use this political power to stimulate the economy out of recession and into a more robust, sustained recovery. Senator Bernie Sanders said it best: “What happens next is up to all of us.” In my view, we should spare no expense in this effort to avoid unnecessary suffering and restore people’s confidence in our institutions, or the economic and political consequences could be dire.

The Economic and Political Need for Meaningful Progress

We discussed how relief and stimulus spending helps everyone. I also asserted that now is precisely the time to deliver this relief, but I am not the only one saying this. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who has been consistently leading the charge on securing COVID relief for working families since the pandemic began, eloquently summarized the need for progressive leadership and meaningful change when he recently spoke on CNN, saying:

Let me just be very clear: as the incoming Chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, I remember what happened in 2010. That is that Democrats, during the 2008-2010 period, controlled the White House, controlled the Senate, and controlled the House [of Representatives]. You remember that? And you remember what happened in 2010?

Democrats got wiped out [in the 2010 midterm elections]. They had the power, but they did not deliver for the American people.

So, what we have got to do right now—no ifs, buts, or maybes—is have an aggressive agenda that says: we understand that millions of people—including my neighbors right here in Vermont—people [are] lining up in their cars in order to get emergency food; people can’t pay their medical bills; people are going deeper and deeper into debt; people are facing eviction; millions of people have lost their jobs.

We have to act, and act now. And the first order of business, by the way, is to pass an emergency COVID-19 bill which, among many other things, says to working-class Americans: we know you’re in pain, and we’re going to get you a $2,000 check for every working-class adult in this country; we are on your side.

We are prepared to take on the big money interests who have so much power. We’re going to expand healthcare to cover the uninsured. We’re going to deal with student debt.

We have got to be bold in a way that we have not seen since FDR in the 1930s.

Not only does Senator Sanders argue for bold progressive solutions to relieve the unnecessary suffering across America, but he also reminds us of the political consequences of failing to do so in the recent past. If Democrats fail to alleviate unnecessary suffering, then faux-populist demagogues like Donald Trump will inevitably seize the opportunity to at least ostensibly campaign on supporting workers, regardless of whether they actually deliver results themselves once elected. I will cover Trump’s incessant lies in further detail in a separate article, but still, I frequently wonder if Trump would have won the election in 2016 if Democrats had more meaningfully helped working families during the previous administration.

Throughout his administration, President Obama acquiesced to deficit hawks’ demands to force economic austerity on working families. In other words, deficit hawks are people adverse to government spending who arbitrarily refuse to use expansionary fiscal policy—like the policies Sanders advocates for—even if it would help everyone, because these they have an irrational fear of deficit spending. Democrats refused to implement bold fiscal policy for working families who struggled in the Great Recession despite previously spending trillions to bail out Wall Street frauds.

President Obama infamously said during his 2010 State of the Union Address that “…families across the country are tightening their belts and making tough decisions. The federal government should do the same.” and he was met with thunderous applause. He then went on to outline certain details of this plan, such as “Starting in 2011, we are prepared to freeze government spending for three years.”

The Democrat-controlled Congress followed suit and codified the complete surrender to deficit hawks by passing The Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 or “PAYGO” rule, mandating a disastrous requirement that any increases in government spending must be offset by increases in tax revenues. This, of course, never seems to apply to Republican bills like the Trump tax cuts, because Republican politicians will simply lie and pull nonsensical numbers out of thin air in an effort to pretend like these tax cuts would “pay for themselves” by spurring economic growth. This promised magical economic growth, by the way, never happened.

Thankfully, a recent House Resolution provides a PAYGO exemption for spending bills relating to the Coronavirus pandemic and the climate crisis. Congressional Democrats appear to have at least somewhat learned their lesson from recent history, though I personally would like to see the PAYGO rule scrapped altogether. I am still cautiously optimistic that we will not repeat the same mistakes that Democrats made during the Obama administration. As a reminder, recall the graph we examined previously showing recession recoveries and how it took more than six years to fully recover from the Great Recession to get an idea of how Obama’s austerity plan worked out.

We should not forget, however, that the primary blame falls on the obstructionist Republican party. Mitch McConnell in particular is a singular force of obstruction, who made the notorious declaration that his priority during the Obama presidency was not to help struggling families or to get the economy back on track, but instead that:

“The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

We should stop trying to unify with Republican politicians whose only apparent goal is to consolidate power for themselves and their wealthy donors—while obstructing relief for working families in the process, if it makes Democrats look bad—and instead focus on delivering meaningful relief for working families. Personally, I agree with President Biden’s White House Chief of Staff, Ronald Klain, who argued that additional Coronavirus relief is bipartisan because, according to polling data, more than two-thirds of Americans, including Republican voters, support it.

The need for additional government spending is supported not only by politicians like Senator Bernie Sanders and economists cited in the Falcettoni and Nygaard paper, but also Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. Even back in October, when he did not yet have the benefit of hindsight from November and December data, Powell accurately predicted that a failure to support strong fiscal policy would “lead to a weak recovery, creating unnecessary hardship for households and businesses”. He further argued, with regards to the amount Congress could spend to avoid these unnecessary hardships, that “The risks of overdoing it is less than the risk of underdoing it… People are always worried about doing too much, and you look back in hindsight and say, ‘Well, we didn’t do too much. We might’ve done a little more and a little sooner.’”

When chosen by President-elect Biden to be Treasury Secretary, former Chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, and the first woman to serve as the Treasury Secretary in U.S. history, Janet Yellen, also had similar thoughts on this economic crisis. She, like Powell and other experts, reminded us of the impact on working families, saying:

Lost lives, lost jobs, small businesses struggling to stay alive are closed for good. So many people are struggling to put food on the table and pay bills and rent. It’s an American tragedy. And it is essential we move with urgency. Inaction will produce a self-reinforcing downturn causing yet more devastation.

Yellen still, whenever asked variations of these same types of questions about deficit spending and debt, continues to argue that we should essentially spend the money now or we will have to dig ourselves out of a deeper economic hole later, and I couldn’t agree more. The economic data reflects this, a growing number of our politicians and appointed officials know how urgently people need relief, we have the political leverage to carry out a proper response to these crises, and voters overwhelmingly support additional relief as well. Even though detractors such as the now Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell predictably derided additional relief as “socialism”, polling data suggests that voters overwhelmingly support additional relief anyway. There is a growing consensus among experts, politicians, and voters alike that more relief is needed, but it still is not necessarily inevitable.

The Debate for Additional Relief Continues

Even though the circumstances are dire, and to many Americans the path forward is clear, not everyone in this country is convinced that we can and must help people get through these difficult times. Despite the fact that neither our economy nor working families have recovered from this pandemic recession; despite the clear economic benefits of the CARES Act, which clearly helped millions of Americans; despite the evidence that we need more of the same types of legislation to alleviate unnecessary suffering and to stimulate the economy; despite the fact that virtually no one ever asks how we can “afford” giving billionaires and corporations trillions of dollars’ worth of tax cuts; and despite the evidence that economic austerity prolongs such unnecessary and avoidable suffering, multiple people have spoken out against Senator Sanders’ policy positions and President Biden’s proposal.

Update: May 31, 2021 – Despite detractors, the growing consensus surrounding additional relief ultimately resulted in the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Although the final draft of the bill did not include every provision Biden initially proposed, many important inclusions were signed into law last March. My third installment in this series details what made the final cut, notable exclusions, and the need to maintain political momentum for further progress. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on the progress we have made since 2020 and the path forward.

Thank you for reading my newsletter and taking the effort to learn about making the world a better place. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can make progress towards a more just economy.

-JJ

Updated 7/14/2022 - Added embedded video of quoted Senator Sanders interview.

Updated 7/13/2022 - Added link to Coronavirus Relief and Economic Stimulus collection.

Updated 6/27/2022 - Updated graph and table captions; italicized signoff; fixed long dashes; added card link to the third article in this series.

Updated 9/20/2021 - Removed date updated from top of the article

Updated 5/31/2021 - Added subscribe, donate, share and comment buttons; updated final paragraph to address changes made to the scope of the subsequent article in this series; fixed and updated links; fixed formatting issues.

On another thought.. would raising the minimum wage nationwide help with recovery? I believe it would l, but I always get the “It would hurt businesses” reply.

I thought this piece was very well written. I understand it, unlike others I try to follow. What would your thoughts be on reoccurring survival checks to those who need it? Much like what Ayana Presley and other progressive democrats have suggested?