Another Record-Breaking Month for Jobs as Infrastructure Deals Progress

July 2021 BLS Jobs Report Analysis

Another 2021 record for jobs was broken in July, according to the most recent BLS Jobs Report. The U.S. economy added a net total of 943,000 jobs, and prior months were also upwardly revised. Instead of 850,000 as the BLS estimated last month, June saw 938,000 added; likewise, May figures jumped to 614,000. The unemployment rate also fell by half a percentage point, reaching 5.4% in July. As you will see in the three-month trends, these positive revisions also mean that the broader trends – which were slowly but surely rising – are now getting a considerable boost.

All three of the most recent jobs figures are even visible on the graph below showing the change in nonfarm employees since the beginning of 2020.

While this is all certainly welcome news, unemployment numbers are known as “lagging indicators” which look back after information comes in, so it doesn’t necessarily tell us how things are going currently, but we have the benefit of hindsight. I mention this because, although I hope the economy can continue to recover, I am growing increasingly concerned about the pandemic once again having different plans for the economy than what we would all prefer. Just as COVID held the reins of the global economy in 2020, so too does it play a central role in 2021. It is important to manage future expectations by keeping the still ongoing pandemic in mind.

Another sobering fact to remember is that we still need to recover millions of jobs before we even approach pre-pandemic levels of employment, and the recovery thus far has not been experienced by everyone. As with past recessions, the pandemic recession affected different groups disproportionately, and I want to briefly discuss some of the statistics which help reveal such dynamics towards the end of this article.

Although it is difficult to say what the future holds – both for the broader economy and for marginalized groups – we can still look back on July’s job figures and glean some insight from the past.

July 2021 Jobs Report

To put a second consecutive month of this year’s highest job growth numbers into perspective, and to also show how positive revisions to prior months’ gains factored in, see the graph below with 2021’s job growth.

July and June are within 5,000 jobs of being tied for 2021’s top month for job growth, with March and May coming in third and fourth place as of the latest jobs report. The leisure and hospitality industry once again accounted for the most jobs added to a single industry, with 380,000 net jobs gained, while local government jobs added 240,000 jobs. More than 90% of these government jobs were in the education sector. This is good news, but with the delta variant of the coronavirus surging, I worry what Fall and Winter months will look like for our educators and students across the country.

Other sectors of the economy also experienced decent growth. The construction industry even added jobs in July, reversing its prior downward trend, with a net increase of 11,000 jobs. Construction and related industries may also receive a long overdue but welcome boost from infrastructure projects currently under negotiation. The Senate passed the bipartisan bill and advanced the budget reconciliation package this week, and I hope we hear more news about these proposals soon.

Together, these infrastructure investments are estimated to create an average of 2 million jobs per year throughout the next decade and boost the economy. Expect an article covering more details of these infrastructure bills in your inbox this month, but take a look at the chart below from Moody’s Analytics to get an idea of the impact these policies could have.

Moving back to the jobs report, one industry that unfortunately did not see a net increase in jobs throughout July was the retail trade sector, which lost roughly 5,500 more jobs than it added. Like in 2020, retail trade was one industry that was sensitive to the pandemic, but with leisure and hospitality adding so many jobs, it’s difficult to say if this was a central factor in the retail industry. Despite losses in this sector, there weren’t many industries that lost jobs, and growth was relatively widespread throughout the economy. The chart from the BLS shown below has the details.

In other bits of good news – which are all too frequently in short supply these days – is another negative trend being reversed throughout July. The percentage of long-term unemployed workers, who have been unemployed for 27 weeks (half a year) or longer, fell noticeably last month. Following a decrease of 560,000 people who are no longer in this category, this brings the total long-term unemployed workers to 3.4 million out of all 8.7 million unemployed workers. As shown in the graph below, this equates to roughly 39.3% of the total.

While this is still a positive development, there are 2.3 million more long-term unemployed workers than there were in February 2020. You’ll notice that the curve above spikes during recessions, like it did in 2001 and 2008, but the most recent recession also saw it plummet first. As you might have already noticed, the dip related to the millions of recent layoffs and otherwise short-term unemployed workers far outnumbering the long-term unemployed people initially. However, as the pandemic continued to maintain a grip on the economy, that trend reversed, and the short-term unemployed steadily saw 27 weeks come and go.

Hopefully the current downward trend continues, especially with the Labor Day expiration date for many unemployment insurance benefits rapidly approaching, but there are also broader trends we should monitor.

Three-Month Trends

Like we discussed previously, July’s gains and positive revisions in prior months’ numbers made a sizeable impact on these broader trends. In the following graph, the bars shown in green represent the three-month averages from the June jobs report, and the blue bars show this month’s averages.

For the first time this year, the U.S. economy has a three-month average above 800,000 jobs. The two prior months also show significant improvement as well, with June surpassing the 600,000 mark. Many industries shared in this job creation, though the construction industry is still turning the corner from multiple months of job losses, but you can see the breakdown by sector in the chart below.

In addition to these three-month trends, I want to also discuss broader trends amongst various demographic groups. Breaking down topline statistics into disaggregated groups helps reveal more nuanced details which can otherwise go unnoticed. For instance, we’ve previously discussed how the pandemic disparately impacted men and women, but we can also look at certain age groups and racial demographics.

Disaggregated Economic Indicators

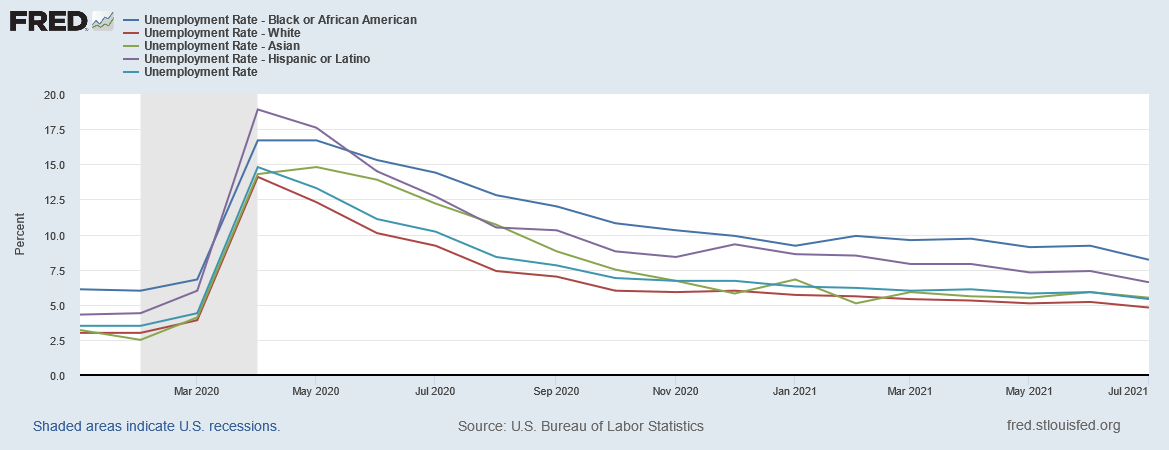

Unfortunately, recessions often disproportionately impact marginalized communities, and the pandemic recession was no exception. You can see in the graph below how unemployment rates varied for different racial groups throughout recent recessions and economic recovery periods. The dark blue line denoting the unemployment rate for Black or African American workers is almost always the highest, save for a brief period in 2020 when the Hispanic or Latino unemployment rate was higher.

The points at which the Hispanic or Latino unemployment rate topped the chart is easier to see in the graph below, which focuses on 2020 and 2021.

While marginalized groups are often disproportionately impacted by economic downturns, July brought mostly good news for everyone. The unemployment rate for Black workers fell an entire percentage point, from 9.2% to 8.2%, the Hispanic unemployment rate fell to 6.6%, and the White and Asian unemployment rates fell by 0.4%, bringing the overall unemployment rate to 5.4% across the economy. Still, the unemployment rate for White workers is below the national average, and all other demographic groups are above that average.

One reason why I qualified these developments as being “mostly” good news is that, as we’ve discussed before, there are other economic indicators in addition to the unemployment rate which help paint a clearer picture of the economy. The labor force participation rate (LFPR) is one such economic indicator. While the unemployment rate fell for all racial groups, each of these groups also saw an increase in labor force participation except for Black workers. Notice the divergence in the graph below.

In June, labor force participation was 0.3% higher for Black workers than for White workers – the only month in which that has occurred in recent history – but that trend reversed in July. Perhaps this is just another indication that monthly changes in these types of indicators is too volatile to pay it much heed, but it is important to not discount broader trends in these disaggregated statistics.

Although certain gaps between these racial groups are narrowing, and some are fortunate enough to have turned a corner since the pandemic began, the recovery is not complete. We cannot allow marginalized communities to be left behind; we should rebuild a better, more just economy. And we should do so, as President Biden has said on multiple occasions, by rebuilding “from the bottom up and from the middle out”.

Another bit of mostly good news the July jobs report brought is a decline in the unemployment rate for both men and women. Throughout 2020, women were disproportionately impacted by several aspects of the pandemic. Women continue to shoulder unequal societal burdens in virtually innumerable ways, but progress is being made in some ways. As you can see in the graph below, although women’s unemployment rate spiked in April 2020, it is currently lower than the national average.

It may be difficult to notice at a glance, but the red line representing the unemployment rate for women dips below the other lines depicted in this graph, and has done so for the past few months.

However, like we just discussed, some of the falling unemployment rates may be attributable to labor force participation. For example, the graph below shows the LFPR for men and women, plus the topline statistic in the middle. While it is a positive sign that the overall LFPR increased, you’ll notice that the LFPR women remained flat while men’s participation rate increased.

The labor force participation rate has not really changed much over the past year, but it is important – especially for readers who are just beginning to learn about labor economics – that the unemployment rate is not the only economic indicator to monitor. It’s also important to know that the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks many such indicators by various demographic categories, and examining these disaggregated statistics rather than topline statistics alone can help reveal important trends. Whether breaking down statistics by racial groups, sex, income quintiles, age, or otherwise taking a closer look at the experiences of different groups, it is important to remember that sometimes topline indicators can paint the economy with overly broad strokes.

One final example I want to examine – which the White House CEA astutely observed in its monthly blog – is the employment-population ratio for people between the ages of 25 and 54 years old. Focusing on this “prime-age” group of workers often filters out the statistical volatility associated with including students and retirees, so this is frequently a preferred indicator for similar reasons that nonfarm employment levels are preferred to total employment. In a graph of this employment-population ratio for prime-age workers shown below, you’ll notice an increase steeper than in any other month this year.

Many of these positive developments are just small improvements in the broader context of the problems facing society, but it is important to acknowledge good news when we are fortunate enough to have some. It is important to monitor new information as it becomes available, but for now, we can celebrate some small victories. Stay safe out there.

Thank you for reading my newsletter and taking the effort to learn about making the world a better place. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can make progress towards a more just economy.

-JJ

Updated 6/27/2022 - Updated captions for graphs and tables

Updated 10/7/2021 - Removed introductory paragraph which was mostly intended for email recipients; also removed update date at the top of the article; italicized sign-off paragraph; changed dark-themed graph for graph with white background & added caption.

Updated 9/3/2021 - Fixed LFPR graph which still demonstrated the trend described, but its data did not extend through July 2021 previously.

Updated 8/11/2021 - Added subscribe, share, and other buttons throughout.