Politicians, and Their Spouses, Should Not Be Allowed to Trade Individual Stocks

Analysis of the Ban Conflicted Trading Act

Senator Rand Paul recently faced public scrutiny for yet another scandal which, this time, involved questionable financial dealings. In February 2020, as the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic was becoming increasingly clear—while former President Trump was, as he himself put it, still “playing it down”—Paul’s wife bought stock in Gilead Sciences. Gilead, a pharmaceutical company, happened to be in the business of producing a certain antiviral drug used to treat COVID-19.

However, while the Senator was supposed to disclose this transaction within roughly a month and a half of the purchase, the public only learned of this in August 2021. In his defense, Paul contends that he filled out the proper disclosure forms on time, but simply forgot to send them. Regardless of when this disclosure was supposed to occur, many are rightly asking whether these transactions should be legal at all.

Should politicians—who have knowledge not available to the public, and are supposed to represent and conduct oversight on behalf of the public—have the virtually unrestricted ability to shuffle their investment portfolios? Insider trading among corporate executives, auditors, and other people with non-public information is prohibited, like Martha Stewart famously discovered. So why are politicians apparently allowed to?

If you have been paying attention to politicians’ financial conflicts of interests like this writer has, you would notice that this is merely the latest incident in a long string of scandals. Even those who have been paying attention may have forgotten certain examples—given the torrential downpour of political conflicts of interests, scandals, and outrages we’ve witnessed recently—so it is worth revisiting certain examples to establish just how rampant these questionable transactions are.

Lastly, I want to discuss proposals to address these conflicts of interest. While I previously wrote about our campaign finance system, how it creates conflicts of interest, and how the For the People Act would help address those problems, these stock market transactions would require different legislative tools to solve. While some decent proposals have been drafted, such as the Ban Conflicted Trading Act, they do not address enough potential conflicts of interest, and—in my view—they could easily be improved.

Keeping this in mind, let’s first revisit some of the more recent examples of politicians profiting on the stock market at our collective expense.

Politicians Playing the Stock Market

Some of the most widely covered, recent instances of politicians engaging in questionable stock market transactions played important roles in the 2020 elections. More specifically, they featured prominently in two Georgia Senate runoff elections which extended into January 2021. Perhaps these transactions took a back seat to Coronavirus relief payments passing through a gridlocked Congress, but even a Fox News poll suggests that the majority of voters were at least somewhat concerned about allegations of insider trading.

Former Senators Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue traded millions of dollars’ worth of stock throughout their Congressional careers, resulting in investigations to determine the legality of such trades. The companies whose stock the Senators bought or sold, the timing of such transactions, and the privileges associated with being Senators all raised red flags.

For instance, Senator Loeffler and her husband reportedly “sold off seven figures’ worth of stock holdings in the days and weeks after a private, all-senators meeting on the novel coronavirus that subsequently hammered U.S. equities.” Between this January 24 private briefing for Senators and mid-February 2020, she and her husband reported 29 stock transactions, including 27 sales and 2 purchases. The purchases, by the way, were stock in companies like Citrix which develop software used for such purposes as working from home.

Meanwhile, Senator Perdue carried out thousands of stock market transactions throughout his Senate career, hundreds of which occurred in the first quarter of 2020. I looked through his Senate Stock Watcher summary page and noticed some patterns. Throughout late February, there are multiple instances of Perdue selling thousands of dollars’ worth of stock in Caesars Entertainment Corporation, owner of hotels and casinos like Caesars Palace. Among his purchases were stock in the vaccine manufacturer Pfizer and streaming companies like ViacomCBS and Disney.

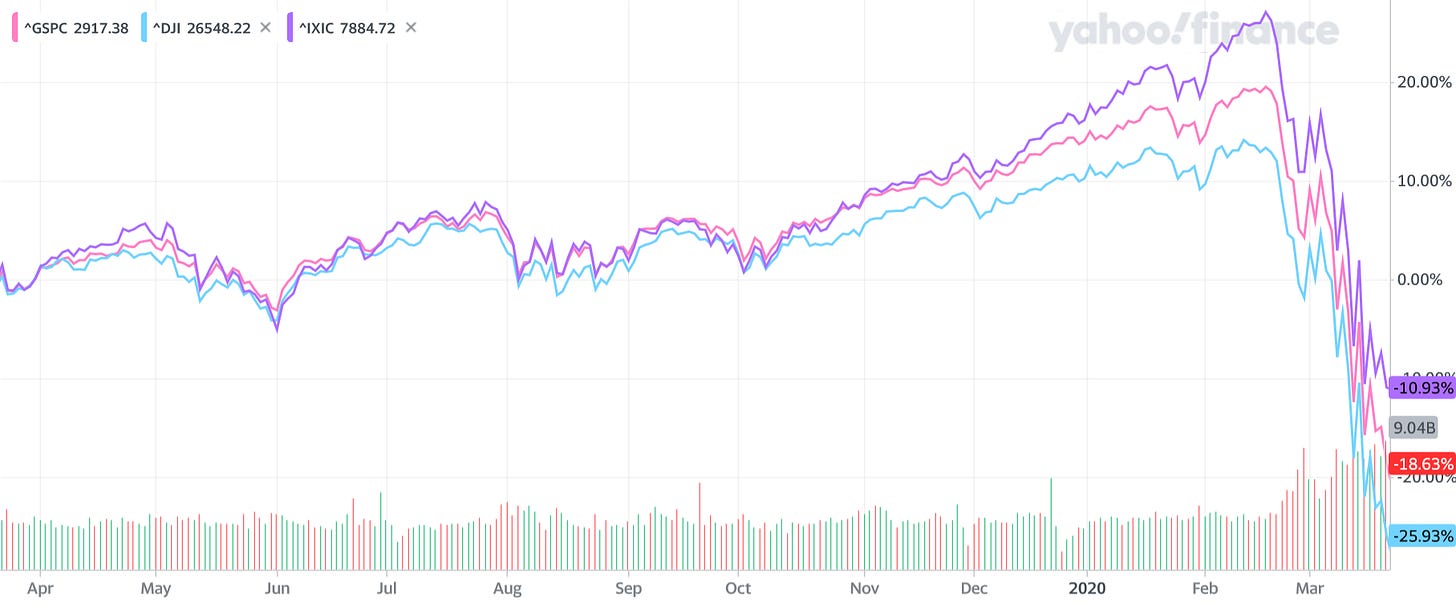

Perhaps the former Senators’ financial advisers simply made prescient observations before these transactions occurred, but this—at the very least—demonstrates the appearance of a conflict of interest. Either way, these Senators shuffled their investment portfolios quite a bit just before the March 2020 stock market dip. Notice the lowest point in several major stock indexes in the graph below:

The broader stock market has since rebounded, and even hit record highs despite Trump’s predictions that the stock market would crash if he lost reelection, but many industries were devastated by the pandemic. These financial maneuverings also raise suspicions of whether certain politicians were downplaying the threat of COVID-19 out of genuine ignorance, or if they were trying to keep the stock market stable long enough to sell off their hotel stocks. The American people deserve to know with certainty that their elected officials represent them, serve their interests, and are not putting public health at risk just to make a buck.

Playing the stock market is not limited to Republican politicians, either. Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein also faced scrutiny when her husband sold millions of dollars’ worth of stock early in 2020. More recently, Representative Nancy Pelosi’s husband purchased several millions of dollars’ worth of Microsoft stock just before a $22 billion government contract was awarded to Microsoft. You’ll notice that these stories frequently involve the spouses of sitting members of Congress.

What’s more, while the pandemic highlighted questionable financial dealings before a catastrophic event unfolded, there have been widespread conflicts of interest throughout “normal” times as well. Many of these members of Congress sit on committees which are responsible for the oversight of companies in which these same Congresspersons have financial stakes. Former Senator Loeffler, for example, sat on the Senate Agriculture Committee. According to this Mother Jones article, that put her in a position to influence regulations impacting a company at which her husband served as CEO:

The company, Intercontinental Exchange (known as ICE), owns and operates a number of financial and commodity exchanges regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which falls under jurisdiction of the Agriculture Committee.

Loeffler’s assignment to the committee seemed a whopping conflict of interest: She still owned between $5 million and $25 million in ICE stock, and her husband, Jeffrey Sprecher, is its CEO. Worse, Loeffler was placed on the committee’s subcommittee on commodities, which has direct oversight of the CFTC. In response to criticism, she left the subcommittee in May but remained a member of the full committee.

Yet one piece of this tale has received little notice. Her conflict of interest was even more pronounced, for while Loeffler was on the commodities subcommittee, the CFTC took several actions that impacted ICE. This means Loeffler was overseeing regulators at the same time they were engaged in activity affecting a company she was intimately tied to as a current shareholder, former executive, and spouse of its CEO.

Keep this story in mind when you hear Republicans crying about regulation. Loeffler’s past also illustrates this point. Before being appointed to the Senate by Georgia’s governor – rather than elected by the people – the article also mentions that while serving as an executive at Intercontinental Exchange, Loeffler complained about “excess regulations” proposed by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Republican politicians rarely decry specific instances of unnecessary bureaucratic red tape; they often want to broadly repeal the types of regulations that make it illegal to pilfer public coffers. Corporate Democrats would probably be happy to see such regulations go as well, but they’re generally less conspicuous about such stances.

Perhaps I’m being idealistic, but I think that we need more rules and regulations which preserve democracy and prevent oligarchic kleptocracy. In other words, I would prefer elected leaders who represent the people over an entrenched, unaccountable nobility who enrich themselves at the public’s expense. But what can be done? We have some laws on the books and some decent proposals for new laws, but they do not sufficiently protect us.

Current and Proposed Political Insider Trading Laws

Despite how things might appear, we do have laws prohibiting certain types of financial transactions, ineffectual in practice though they may be. The STOCK Act of 2012, for instance, is why Senator Rand Paul was required to disclose his wife’s purchase within 45 days—rather than 16 months—of the initial transaction.

The STOCK Act—or the “Stop Trading On Congressional Knowledge Act”—also extends certain restrictions originally designed to prohibit corporate executives and other Wall Street “insiders” from trading on non-public information, and applies these restrictions to politicians. While this sounds useful in theory, these restrictions are difficult to enforce in practice. Without going into too much legalese and complicated details, let’s examine some general reasons why such questionable transactions continue to happen despite the STOCK Act.

This article from NBC News quotes a lawyer who explains some of the legal pitfalls:

“They'll never… prosecute anybody for this, if they have to penetrate a committee to find out if that's where the information came from. That's speech-or-debate protected territory,” said Stan Brand, a Washington lawyer and former U.S. House general counsel.

The “Speech or Debate” clause to which he was referring is part of our Constitutional system of checks and balances. It essentially protects our legislators from being arrested or improperly questioned by the other branches of government while debating or drafting laws. However, because of these Constitutional protections, this clause would also give any member of Congress a strong upper hand in an insider trading case, and we apparently have yet to see how a court would handle such a case.

The article went on to describe situations where the Act has worked, though:

Members of Congress can nonetheless be prosecuted for insider trading when the information they act on comes from a company, not through the legislative process. Former Rep. Chris Collins, a New York Republican, was sentenced to 26 months in prison in January after he admitted revealing inside knowledge to his son about a drug company's stock that was likely to fall. Collins learned of the information because he served on the company's board.

The Act evidently can restrict certain stock transactions, but we continue to hear allegations of questionable practices. I am doubtful that Senator Paul will face any repercussions for his failure to disclose his wife’s stock purchase; I also doubt that Speaker Pelosi’s Microsoft investment will do anything but pay dividends. Senators Loeffler, Perdue, and Feinstein, and other politicians were all investigated, but no violations were found. In fact, these types of investigations rarely result in disciplinary action. At a time when confidence and trust in Congress is at historic lows, perhaps it is time to improve restrictions so that even the appearance of a conflict of interest is far less common.

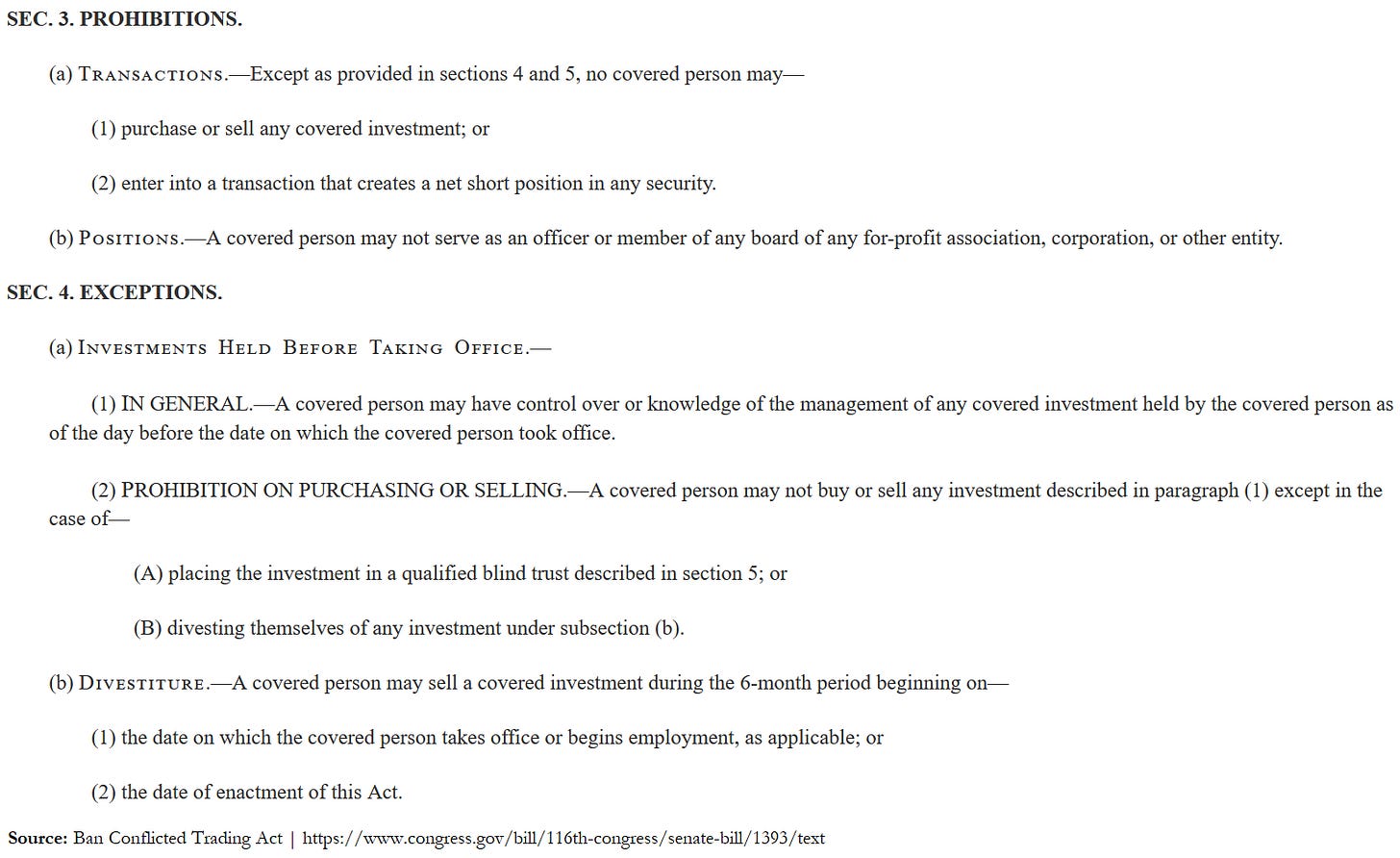

To enact more comprehensive restrictions, members of the House and Senate have introduced a bill called the Ban Conflicted Trading Act. This Act would prohibit members of Congress and certain staff from trading individual stocks at all, except when selling previously owned investments for the purpose of divesture within six months of taking office. Politicians could still own investments, but they would no longer be able to buy or sell specific stocks, and would relinquish that authority to a blind trust, or a financial expert who makes investment decisions on their behalf. Some politicians claim to already use blind trusts for their investments, but this would make doing so a requirement rather than voluntary.

It would also prohibit these politicians from serving on the boards of for-profit corporations and other business entities. The bill’s text is rather short and concise compared to other bills I’ve covered, and would probably fit on a few pages. You can see the core provisions of the Act in the screenshot below.

However, there is one section that, in my opinion, is too short, and too limited in scope, to address the recurring problems we face with politicians having financial conflicts of interest. Recalling the examples of Congressmembers we discussed earlier, look at the screenshot below describing people who are covered under this Act and see if you can figure out who else should have been included.

This definition only covers “a sitting Member of Congress” and certain staff members; it says nothing about their spouses or other family members. Even if this were enacted, we would probably continue to hear stories about people like Senator Paul “forgetting” to file his wife’s financial disclosures. What can be done, though? I don’t claim to have all the answers, but I can offer suggestions from what I’ve seen in the accounting industry.

Rules for Family Members of Covered People

We discussed earlier how these “insider trading” restrictions are based on Wall Street laws and regulations covering business executives and other people with non-public information. Another group of people who are not allowed to trade on such non-public information is the auditors who examine public companies’ financial statements to ensure they are fairly stated for public use.

These auditors are the people trying to, for example, prevent another Enron situation from occurring, where a company defrauds the public into thinking the company is more profitable than it really is. Following the fallout after Enron’s collapse—whose financial problems went undetected for several years due to its auditing firm, Arthur Anderson, signing off on its financial statements despite numerous red flags—stronger regulations were passed to help prevent such conflicts of interests between auditors and client companies.

Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, also known as the “Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act”, in response. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act is far from perfect, and has its fair share of critics—some of my former accounting professors included—but it does many things right. I won’t go into the specific details of all the requirements, but the provisions aimed at increasing independence between auditors and their client companies are noteworthy.

The idea is that, if auditors are supposed to help protect the public—who often invest their retirement funds into the stocks and bonds of such publicly traded companies—then the auditors should be as impartial as possible. There is already an inherent conflict of interest due to the auditors having to judge their own clients fairly and impartially. Obviously, if the client company were to continue doing business, that means the auditors stand to rake in more revenue by performing audit and attestation services. The auditors’ impartiality need not be further impaired by, for instance, allowing individuals conducting the audit to own stock in these client companies.

There are rules and regulations covering auditors and other people with non-public information so that these conflicts of interest do not occur. Some rules exist to prevent even the appearance of a conflict of interest. These rules do not stop at applying to people within the auditing firm, either. There are separate rules for the friends and families of these individuals. See, for example, the excerpt below from the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct describing certain rules for the family members of covered people.

Immediate family members of a covered member, such as an auditor working on a particular client, must generally adhere to the same independence rules as the auditor themselves. Such a rule for immediate family members would include the spouse of the auditor. This helps prevent an auditor from improperly signing off on the financial statements of a company in which their spouse is invested. There are even rules regarding the friends of certain individuals with non-public information, as shown in the excerpt below.

There are some instances where applying various safeguards can help mitigate risks to a person’s independence, but in many cases, certain investments and arrangements are avoided altogether out of an abundance of caution. Perhaps now our politicians need to likewise exercise an abundance of caution and avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest with their investments.

I don’t mean to say that these rules are perfect, that they prevent every threat to impartiality in the accounting industry, or that applying such rules to our politicians would prevent all future financial conflicts of interest. But such rules would be a good place to start making progress towards a more representative government. Just as accountants should not be invested in the companies they audit, so too should our politicians not be invested in the companies their legislation and oversight impact.

We should pass the Ban Conflicted Trading Act and include language in it which covers the family members—or at least the spouses—of sitting politicians.

February 2022 Update

This February, new bills gained bipartisan support in Congress which incorporated some of the changes I advocated for in this article. I covered some of the details surrounding the Ban Congressional Stock Trading Act in the February edition of the Economic Justice and Progress Newsletter.

Although no proposed bill has been signed into law yet, I will continue to support this type of long overdue, commonsense legislation and inform readers of any progress.

Thank you for reading my newsletter and taking the effort to learn about making the world a better place. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can make progress towards a more just economy.

-JJ

Updated 6/28/2022 - Added a link to, and summary of, the February update.

Updated 2/11/2022 - Pluralized Senators’ financial advisers when discussing former Senators Loeffler and Perdue to make it clearer that both Senators used financial advisers at the time questionable stock transactions occurred.

Updated 1/28/2022 - Replaced several hyphens with long dashes; fixed phrasing in an introductory paragraph regarding insider trading.