President Biden delivered a speech in Philadelphia – the birthplace of the U.S. Constitution – on July 13, 2021, in which he described the ongoing assault on U.S. democracy as a “test of our time”. Many have described our predicament as an assault on democracy itself, but now even the President has publicly acknowledged that this is what we are living through, saying:

There is an unfolding assault taking place in America today — an attempt to suppress and subvert the right to vote in fair and free elections, an assault on democracy, an assault on liberty, an assault on who we are — who we are as Americans.

If we are to rise to this occasion and ensure that we have a functioning democratic republic, Congress must pass the For the People Act. As President Biden said during the speech:

…that bill would help end voter suppression in the states, get dark money out of politics, give voice to the people at the grassroots level, create a fairer district maps, and end partisan political gerrymandering.

Last month, Republicans opposed even debating, even considering [the] For the People Act. Senate Democrats stood united to protect our democracy and the sanctity of the vote. We must pass the For the People Act. It’s a national imperative.

However, what he did not mention was how a Senate majority could be blocked by anti-democratic obstructionists who want to undermine progress, regardless of who they hurt in the process. Republican Senators abuse a Senate rule – which neither appears in the Constitution, nor was such a rule supported by our nation’s founders – called the filibuster.

President Biden did mention during a recent townhall event that he would support returning to a “talking” filibuster, where Senators would actually be required to stand and debate the bill under consideration. This would be an improvement over our current system, which basically allows for a group of 41 Senators to block most legislation by merely threatening to filibuster. Still, there is a reason why Alexander Hamilton called such a rule “a poison” rather than “a remedy” for partisanship, and I personally think it should be abolished altogether. I will cover the filibuster and obstruction at length throughout the next article in this series, but I want to focus on another important matter in this entry.

This important matter picks up where my last article – which covered voting rights, election security and integrity provisions in the For the People Act – left off, and continues onto the next section. As a reminder, the For the People Act is divided into three sections: voting, campaign finance, and ethics reform. We covered the first section last time, so this article will focus on campaign finance reform, and my next article in this series will cover ethics reforms. I also want this upcoming article to set the stage for the path forward, describing what it will take to pass the Act, and how the filibuster and its enablers stand in the way.

To understand why campaign finance and ethics reforms are so important, we must first understand how corruption became so rampant in our political system. I could, and probably will eventually, write an entire series about the ways in which vast wealth and unethical practices have corrupted our democratic processes. In my view, a central cause of our unjust economy is the vicious cycle of the wealthy and corporate elite using their political influence to further enrich and entrench themselves economically and politically. This overview should serve as good a starting point as any for those who are unfamiliar with such systemic flaws. While there have been many steppingstones along America’s political descent, none were quite as consequential as the Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

The Citizens United Decision

In 2010, the Supreme Court made a ruling that basically opened the floodgates for unlimited corporate spending in elections. The court case came about when the Federal Election Commission (FEC) prevented a conservative nonprofit organization called “Citizens United” from promoting a video criticizing Hillary Clinton in 2008 – on the grounds that doing so would essentially be illegal corporate electioneering – and eventually the Supreme Court had to evaluate the constitutionality of the situation. You can read more background information in this Brennan Center summary, but the Supreme Court ruling is full of tortured logic.

The Citizens United decision essentially said that preventing the promotion of a political video would restrict corporations’ ability to spend money on elections, and that this type of political spending is protected speech under the First Amendment of the Constitution. Therefore, the government cannot intervene in such cases. The ruling was made by a 5-4 vote, with the conservative majority voting for unlimited corporate spending in elections and the liberal judges dissenting. In his dissent, Justice Stevens argued that this decision goes against more than 100 years of campaign finance reform, citing several laws passed throughout the decades, including the Tillman Act of 1907.

The conservative majority argued that restricting the ability to “spend unlimited amounts on independent [political] expenditures” would be “censorship to control thought.” Instead of putting limits on total spending, the majority advocated a compromise: “The Court has explained that disclosure is a less restrictive alternative to more comprehensive regulations of speech.” Again, by speech, they mean corporate spending in elections. Even then, it is generous to say that these conservative Justices are merely incompetent and not complicit in effectively legalizing electoral corruption, especially when considering how many loopholes exist in our disclosure requirements.

Political Action Committees and Dark Money

Justice Stevens predicted the long-term outcome of the Citizens United decision, saying that, “The Court’s ruling threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation.” This reality – where far too many of our politicians are bought by frequently untraceable “dark money” – stems directly from the Supreme Court’s decision to reject spending limits and instead rely on piecemeal, easily circumvented disclosure laws.

Political action committees, or PACs, have existed for decades. In fact, PACs trace their roots to the labor movement, with the first PAC being the CIO-PAC: the Congress of Industrial Organizations – Political Action Committee. However, the Citizens United decision led to the creation of a new type of PAC which no longer has to follow the same types of rules that PACs of the past had to follow.

While researching information for this article, I went back to some of the first reporting which made me aware of these campaign finance laws. To this day, I still think they are also some of the best examples of U.S. campaign finance coverage. Stephen Colbert, who began hosting the Late Show after David Letterman’s departure, had a satirical news show during the Citizens United decision, called “The Colbert Report”. Colbert started his own PAC as part of an exposé series highlighting what became legal after the Citizens United decision. He reported on these developments in an informative yet entertaining manner, with a sort of gallows humor highlighting how far our political system has fallen, and offering prescient glimpses of future election cycles.

Soon after forming a PAC, Colbert began to encounter legal issues that would have been unlawful before the Citizens United decision. Colbert discussed PAC logistics with his lawyer, Trevor Potter – who previously chaired the Federal Election Commission, so he knows a thing or two about campaign finance laws – throughout several episodes of the Colbert Report. During one such episode, Potter raised the concern that Viacom Inc., owner of Comedy Central, would be giving “in-kind” contributions to Colbert’s PAC when airing Colbert’s show, paying his staff, and otherwise otherwise participating in the production of the Colbert Report.

Before the Citizens United decision, these in-kind contributions would be against the law. However, Colbert’s lawyer proposed a work-around. Here’s how the conversation went:

Potter: There is another approach you could try… There’s something called a “Super PAC”.

Colbert: What’s a Super PAC? Is that like a PAC that got bitten by a radioactive lobbyist? What’s a Super PAC?

Potter: Well, you’ll remember that last year there was a furor over the Supreme Court’s decision in the Citizens United case –

Colbert: Oh, that said that corporations are people, and people have free speech; therefore, money is free speech, and corporations can give unlimited money to political issues?

Potter: Yes, that was the key ending… For the first time, corporations can spend an unlimited amount of corporate money, and labor money, in federal elections. The Federal Election Commission said, well, if they can spend money independently, which the Supreme Court just said they can, then we ought to give them a vehicle to do it in PAC form, so that they can do it together. So the Federal Election Commission created, last summer, what they call an independent-expenditure-only committee, which is commonly known as a Super PAC…

Colbert: So, how do I turn this [PAC] into a Super PAC?

Potter: All you have to do is send a cover letter to the Commission that says, “This PAC is actually a Super PAC.” […]

Colbert: So, here’s my form. That’s a regular PAC that cannot take money or a gift in kind from Viacom.

Potter: Right.

[Colbert places the cover letter on top of the PAC forms.]

Colbert: Now it’s a Super PAC?

Potter: Right.

[Colbert removes the cover letter from the top of the PAC forms.]

Colbert: PAC…

[Colbert places the cover letter back on top of the PAC forms.]

Colbert: Super PAC!

A simple piece of paper, a new designation, and now suddenly more than a century of legislation and precedents are basically irrelevant. And remember, the Supreme Court argued that Super PACs are fine because they are required to disclose their donors. Colbert and his lawyer once again televised just how easily these disclosure requirements can be circumvented.

In another episode of the Colbert Report, they discussed how corporations organized under Section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code – a law which primarily relates to non-profit, tax-exempt civic or “social welfare” organizations – can be used to skirt disclosure requirements. Colbert once made the witty observation that, when used for this purpose, these organizations are “like a Secret Santa, if Santa wanted to weaken environmental regulations.” He wasn’t wrong.

Take, for instance, the ExxonMobil executive who was filmed by Greenpeace talking about how they use “shadow groups” to undermine climate science. Meanwhile, they put out positive corporate PR campaigns advocating for beneficial policies like carbon pricing with the hopes of laundering their public image. Many corporations want to surreptitiously fund causes which increase their bottom line but might cause public outrage.

Colbert’s lawyer suggested this might be why Colbert’s Super PAC hadn’t gotten any corporate donations by the time this particular episode aired.

Potter: They’d be nervous about giving [money] in a way that their name is publicly disclosed. People might object to what they’ve done – their shareholders, their customers…

Colbert: Okay, so that’s where a [Section 501] (c)(4) comes in. A corporation or an individual can give to a (c)(4) and nobody gets to know that they did it. Right? […]

Potter: That’s right, and that money can be used for politics!

Colbert: Oh, great! That’s good too! As long as it goes through me, it can go to anything it wants. So how do I gets me one, Trevor?

Potter: Well, lawyers often form Delaware corporations – which we call “shell corporations” – that just sit there until they’re needed…

Colbert then created an anonymous shell corporation – which was literally called “Anonymous Shell Corporation” – and could make political contributions throughout the 2012 election without disclosing anything until May 2013.

Colbert: So I could get money for my (c)(4), use that for political purposes, and nobody knows anything about it until six months after the election?

Potter: That’s right, and even then, they won’t know who your donors are.

After hearing this news, Colbert – who played a satirical conservative alter-ego on the show – responded, “That’s my kind of campaign finance restriction!” He then proceeded to do a similar bit as in the previous segment, where he would place his form on a stack of paper and lift it off, showing the difference the Citizens United decision made for his Super PAC.

Colbert: So without this [form], I am transparent. With this, I am opaque. Without it, you get to know. With it, you go to hell!

And what did this 501(c)(4) designation allow Colbert to do with his anonymous money?

Potter: That (c)(4) could take out political ads, attack candidates or promote your favorite ones, as long as it’s not the principal purpose for spending its money.

Colbert: No, the principal purpose is an educational entity, right?

Potter: There you go.

Colbert: I’m going to educate the public that gay people cause earthquakes.

Potter: There are probably some (c)(4)s doing that.

Then Colbert asks the key question, highlighting the central loophole in these disclosure requirements.

Colbert: Can I take this (c)(4) money and then donate it to my Super PAC?

Potter: You can.

Colbert: …Well, wait, wait, Super PACs are transparent!

Potter: Right…

Colbert: And the (c)(4) is secret!

Potter: Uh-huh…

Colbert: So I can take secret donations of my (c)(4) and give it to my supposedly transparent Super PAC!

Potter: And it’ll say, “Given by your (c)(4)”.

Colbert: What is the difference between that and money laundering?

Potter: It’s hard to say.

I agree. It is hard to say what the difference between this campaign finance system and money laundering, legalized bribery, and any number of other crimes of corruption would be.

Unlimited amounts of untraceable funds circulate throughout our political system, but even if we can’t trace the sources, we can often figure out where it’s going. So, what is this dark money being spent on? I could probably write a series of articles on this subject as well, but I will discuss a few examples, including one which Colbert covered during the 2012 election cycle.

Karl Rove – another Republican operative who tried to launder his own reputation by periodically speaking out against Trump, despite effectively paving the way for someone like Trump to seize power – was one of the early post-Citizens United campaign finance trendsetters with his American Crossroads Super PAC and Crossroads GPS 501(c)(4). Using untraceable money – $20 million of which came from just two individual $10 million donations, and they could have even been from the same donor, for all we know – Rove funded groups lobbying against state-level efforts at cleaning up campaign finance. As Colbert remarked, “So, that’s Karl Rove giving anonymous political money to help keep political money anonymous.” This corrupt system will continue to further entrench itself, and disenfranchise the average voter, unless we intervene.

In addition to easily circumvented disclosure laws, which the conservative Supreme Court Justices argued made corporate spending limitations unnecessary, there are also laughable restrictions against coordination between these organizations and candidates. Colbert filmed a commercial showing just how ineffectual such restrictions are in practice. Even though the candidate appeared in the ad, they used the pretext of raising awareness for a certain issue, rather than saying, “Vote for this guy!” It’s the same type of reasoning that Trump would use, where it’s apparently not corruption unless you shout, “I am doing a corrupt act for personal gain!”

All of this would not have been possible without the Citizens United decision, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

For the People Act and Citizens United Findings

I am not alone in my estimation that the Citizens United decision and related court cases have been devastating for participatory democracy in the United States. The For the People Act specifically mentions Citizens United, and contains a section dedicated to outlining the problems it caused, which is embedded within the section proposing campaign finance reforms designed to address these problems. It even asserts that, if the courts continue to rule against restrictions on corporate campaign financing, then a Constitutional Amendment is worth pursuing.

This section of the For the People Act begins by echoing the words of the Founders, asserting that, “The American Republic was founded on the principle that all people are created equal, with rights and responsibilities as citizens to vote, be represented, speak, debate, and participate in self-government on equal terms regardless of wealth.” It goes on to declare that, if only the wealthy can participate in this system, then the rights guaranteed to all in the First Amendment are merely an illusion.

Campaign finance laws, the writers of this bill argue, are central to upholding these First Amendment principles. While the First Amendment does not allow the government to censor voices, it does not allow voices to be drowned out by a firehose of corporate propaganda, either. If campaign ads are engaging in “free” market competition – where innumerable voices are trying to be heard in a limited number of commercial breaks, seen in a finite number of ad spaces, and otherwise capture voters’ limited attention – then purveyors of political ad space essentially become auctioneers. Average citizens, whose real wages have stagnated for decades, must compete with the de facto aristocracy, whose wealth has exploded while their effective income tax rates decreased.

The writers also denounce the Supreme Court’s rulings in the Citizens United case and related decisions. Just as Stephen Colbert demonstrated in real time what these decisions enabled by publicly abusing campaign finance laws, the For the People Act decries these rulings’ impact, saying, “These flawed decisions have empowered large corporations, extremely wealthy individuals, and special interests to dominate election spending, corrupt our politics, and degrade our democracy through tidal waves of unlimited and anonymous spending.” Because such spending is anonymous and often untraceable, and so many corporations have multinational ownership structures, the Act also raises the concern that we have no idea how much foreign spending is influencing our elections.

Due to limits on “outside spending” – spending which technically is not directly coordinated with the candidates themselves, but handled by “independent” organizations, as we discussed previously – being eradicated by the Supreme Court’s decisions, this type of spending has predictably skyrocketed in recent election cycles. The For the People Act cites a greater than 700% increase in outside spending between the 2008 and 2020 election cycles. It further states that, “Spending by outside groups nearly doubled again from 2016 to 2020 with super PACs, tax-exempt groups, and others spending more than $3,000,000,000.” That is three billion dollars with which average citizens must compete to be heard.

If average citizens were to try to compete with billions in political spending, it would likely take millions of individual contributions. For example, if everyone chipped in $27 – the average amount Bernie Sanders received from supporters at one point in his presidential campaigns, although that amount likely fluctuated over time – it would take over 111 million people, or roughly one-third of the U.S. population, to be able to raise such a vast sum.

While we’re on the subject of Senator Sanders, take a look at his 2020 outside spending page on OpenSecrets.org, a website run by an independent nonprofit group researching campaign contributions. I’ve included an excerpt from that page below, showing the largest amounts of spending by groups for or against Sanders. Notice how the millions of dollars spent by groups opposed to his candidacy eclipsed the thousands raised by groups supporting him?

Interestingly, when I looked into this “Big Tent Project Fund” to learn more about the group, I found this information in a Politico article published during the 2020 presidential primaries:

THE BIG TENT PROJECT -- a Dem 501(c)(4) group aimed at boosting moderates -- has $1 MILLION to spend in South Carolina and Nevada to bash Sen. BERNIE SANDERS (I-Vt.). The group’s executive director is JONATHAN KOTT, a former top aide to Sen. JOE MANCHIN (D-W.Va.). (C4s don’t have to disclose donors, so we won’t know who is behind this.)

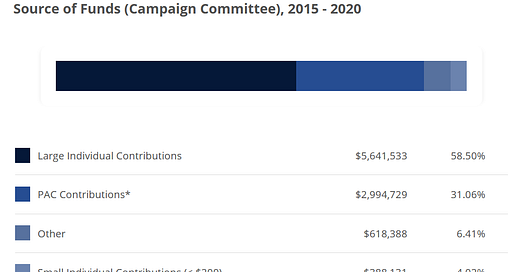

Speaking of Joe Manchin – who once voiced outright opposition to the For the People Act, and is now trying to advocate for a version of the Act without any campaign finance or ethics reforms – why might he be opposed to such reforms? And why might his former top aide be opposed to Bernie Sanders? Perhaps it has something to do with how Manchin raises campaign funds, and how that differs with how Senator Senders raised his. See this OpenSecrets.org summary below showing Manchin’s fund raising through 2020, which mostly related to his 2018 reelection campaign.

Manchin Senate Campaign Finance Summary

Notice how nearly 90% of Manchin’s funding came from large contributions and PACs, and how barely 4% came from small individual contributions? Let’s contrast this with how Bernie Sanders raised his funds.

Sanders Presidential Campaign Finance Summary

The majority of Bernie’s campaign funds came from small donations under $200, and he did not take a single penny of PAC money. Furthermore, as mentioned in the “Findings related to Citizens United” section, “When it comes to policy preferences, our Nation’s wealthiest tend to have fundamentally different views than do average Americans when it comes to issues ranging from unemployment benefits to the minimum wage to health care coverage.” Perhaps this helps explain why Senator Manchin was among the seven democrats who voted against increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour during the American Rescue Plan negotiations. I also can’t help but suspect that these fund-raising dynamics play a role in Manchin’s opposition to the For the People Act.

To get a better idea of why people like Joe Manchin would be opposed to the campaign finance reforms this bill would enact, let’s take a closer look at the provisions in the For the People Act.

For the People Act – Campaign Finance Reforms

One of the first campaign finance reforms included in the For the People Act involves curtailing the influence of illicit money has on our elections. You might remember hearing about either the “Panama Papers” or the “Paradise Papers” a few years ago, which helped reveal the role of “shell companies” being used to conceal the sources of laundered money around the world. While this bill may not address every risk posed by such practices, it certainly proposes several good first steps.

If enacted, it would set stricter requirements for foreign lobbyists, or people effectively advocating for the interests of foreign countries. Perhaps this type of requirement would have prevented, or at least helped alert authorities to, the activities of Trump lackeys like Paul Manafort and Tom Barrack. At the very least, enacting these reforms should mean that red flags would be raised sooner, since the public only learned about the extent of Tom Barrack’s alleged crimes just days before this article was published. The Act would further restrict candidates from providing foreign powers with campaign data, such as when Manafort shared Trump campaign polling data with a Russian operative.

In addition to increasing restrictions on what can be given to people acting on behalf of other countries, the For the People Act clarifies rules regarding what can be received by foreign sources. Perhaps Trump would not have had the luxury of choosing whether or not to disclose his foreign contacts during the 2016 election if this were already the law.

Recall, for example, how Trump said during an interview with George Stephanopoulos – when asked if a candidate should report information coming from a foreign agent – that, “It’s not interference, they have information – I think I would take it.” He added, “If I thought there was something wrong, I’d go maybe to the FBI – if I thought there was something wrong.”

Thankfully, the wording of the For the People Act says that the political committee “shall” report this type of information, and doesn’t qualify it by having an “if you think there was something wrong” clause. All too frequently, people like Trump see nothing wrong with something that benefits themselves, regardless of who it might harm.

The For the People Act also contains a provision called the DISCLOSE Act, or the “Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light On Spending in Elections Act of 2021”. Among several campaign finance disclosure requirements, this Act appears to directly target some of the loopholes Colbert reported on. According to the Senate Summary, it:

Requires super PACs, 501(c)4 groups and other organizations spending money in elections and on judicial nominations to disclose donors who contribute more than $10,000. Shuts down the use of transfers between organizations to cloak the identity of the source contributor.

It also requires certain organizations to report “campaign-related disbursements” within 24 hours of spending $10,000 or more for such expenditures. The DISCLOSE Act even contains provisions to safeguard donors from harassment or threats. While I certainly agree that the government shouldn’t be “doxing” people who contribute to election campaigns, voters still have a right to know whose interests our elected officials might serve.

Many other provisions in the For the People Act essentially modernize existing campaign finance laws, making it clear when longstanding principles apply to new technology. For instance, the Act prohibits the use of “deepfakes” in political ads, which could otherwise be used to spread disinformation. It also requires more conspicuous disclosure of disclaimers on certain online content. My hope is that this will make social media posts by political operatives easier to distinguish from other posts, just like how TV commercials must clearly state who paid for a political advertisement.

There are other proposed disclosure requirements for large, powerful organizations susceptible to the corrupting influence of unlimited, untraceable funds. Such requirements would include corporations disclosing campaign funding to their shareholders, government contractors disclosing their political spending, and Presidential Inaugural Committees disclosing their expenditures with the aim of restricting those funds from being spent on anything but inauguration. In addition to disclosure requirements increasing transparency for wealthy interests, the For the People Act also includes provisions to empower small donations.

Several of these provisions would help the average voter make a bigger difference, as well as candidates who are not funded by corporations and billionaires. A new 6-1 matching system for small donations would be introduced for certain Congressional and Presidential elections, adding $30 to a $5 donation, or $135 to one for $27. These small donations would be matched with funds raised by imposing fines on “corporate lawbreakers and wealthy tax cheats”, according to the Senate Summary. This means that, while the system would use public funds, technically no taxpayer dollars would be used in funding these campaigns.

Other changes to campaign finance laws would make it easier for average citizens to challenge wealthy, entrenched incumbent politicians. One change would allow for campaign funds to be used for childcare, health insurance costs, and other expenses that might otherwise prevent working people from being able to afford running a campaign. This way, candidates from all walks of life could run for office without having to simultaneously raise campaign funds and then start a separate GoFundMe for personal expenses.

The final section of campaign finance reforms deals with oversight to ensure that these new laws, and other existing laws, are followed. These oversight provisions include measures to reform the FEC, requirements for the FEC to issue recommendations for getting political committees to issue disclosures before elections (rather than months after they end), stop Super PACs from coordinating with candidates – like Colbert showed was all too easy – and requirements for candidates to disburse their campaign funds by a certain deadline, so that they can’t be kept indefinitely.

If these new laws can be implemented and enforced, I’m confident we could make significant progress towards a political system that works for everyone, and not just the wealthy.

The Path Forward

As of the time this article was published, the For the People Act is still being obstructed, and only part of the Democratic party is treating this with any urgency. In my next article, I will finish covering the Act’s remaining provisions, and I will outline the reasons why the filibuster should at least be modified or, ideally, abolished.

Like many progressives are saying, we have a choice: we can either choose to preserve the filibuster as it currently exists, or we can choose to preserve and revitalize democracy.

Thank you for reading my newsletter and taking the effort to learn about making the world a better place. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can make progress towards a more just economy.

-JJ

Updated 6/28/2022 - Added captions to images; italicized signoff message.

Updated 9/14/2021 - Removed updated date at top of the article to make more room for preview text in embedded article previews.

Updated 7/26/2021 - Added subscribe, share etc. buttons throughout.